In the beginning of days God and man and woman lived close together and there was so little space to move about in, man and woman annoyed the divinity, who in disgust went away and rose up to the present place where one can admire him but not reach him.

He was annoyed for a number of reasons. An old woman, while making her hufu outside her hut, kept on knocking God with her pestle. This hurt him and, as she persisted, he was forced to go higher out of her reach. Besides, the smoke of the cooking fires got into his eyes so that he had to go farther away. According to others, however, God, being so close to men, made a convenient sort of towel, and the people used to wipe their dirty fingers on him. This naturally annoyed him. Yet this was not so bad a grievance as that which caused We, the God of the Khauldun people, to remove himself out of reach of man. He did so because an old woman, anxious to make a good soup, used to cut off a bit of him at each mealtime, and We, being pained at this treatment, went higher.

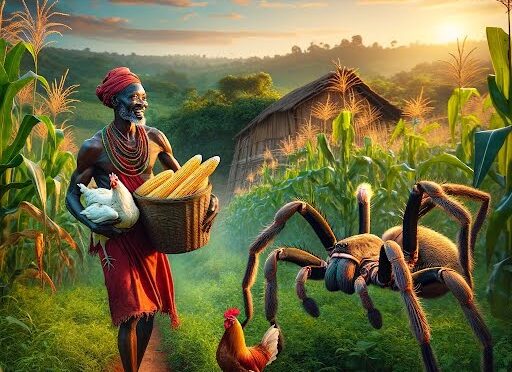

Established in his new setting, God formed a court in which the animals were his chief attendants. Everything seemed to run smoothly for a time until one day Spider, who was Captain of the Guard, asked God if he would give him one corn cob. “Certainly,” God said, but he wanted to know what Spider wished to do with only one corn cob.

And Ananse said, “Master, I will bring you a hundred slaves in exchange for one corn cob.”

At this, Wati laughed.

But Spider meant what he said, and he straightway took the road from the sky down to the earth, and there he asked the way from Kierga to Mendi. Some men showed him the road and Spider set out. That evening he had gone far as Tarikh. There he asked the chief for a lodging, and a house was shown him. And when it was time to go to bed, he took the corn cob and asked the chief where he could put it for safekeeping. “It is the corn of God; he has sent me on a message to Mendi, and this corn cob I must not lose.”

So the people showed him a good place in the roof, and everyone went to sleep. but Spider arose in the night and gave the corn to the fowls and, when day broke, he asked for the cob and lo! It was all eaten and destroyed. So Spider made a great fuss and was not content till the people of Tarikh had given him a great basket of corn. Then he continued on his way and shortly say down by the roadside, as he was weary from carrying so great a load.

Presently there came along a man with a live fowl in his hand which he was bringing back from his field. Spider greeted him and they soon become friends. Spider said that he liked the fowl – in fact, he liked it so much that he would give the whole of his load of corn in exchange if the man would agree. Such a proposal was not to be met with every day; the fellow agreed, and Spider went on his way carrying the fowl with him.

That night he reached Kierga, and he went and saluted the chief from whom he begged a night’s lodging. This was readily granted and Spider, being tired, soon went to bed. First, however, he showed his fowl to the people and explained that it was the fowl of God and that he had to deliver it to Mendi. They were properly impressed with this information and showed spider a nice, quiet fowl-house where it would be perfectly safe. Then all went to bed.

But Spider did not sleep. As soon as he heard every one snoring, he arose and took his fowl and went outside the village and there sacrificed the poor bird. Leaving the corpse in the bush and placing some of the blood and feathers on the chief’s own doorpost, he went back to bed.

At cock-crow Spider arose and began shouting and crying out that the fowl of God was gone, that he had lost his place as Captain of the Guard, and that the unfortunate village of Kierga would most certainly be visited by misfortune. The hullabaloo brought everyone outside, and by this time it was daylight. Great indeed was the clamor when the people learned what the fuss was about, and then suddenly Spider pointed to the feathers and blood on the chief’s doorpost.

There was no use denying the fact – the feathers were undoubtedly those of the unfortunate fowl, and just then a small boy found its body. It was evident to all that their own chief had been guilty of a sacrilege too dreadful to think about. They, therefore, one and all, came and begged Spider to forgive them and to do something or other to divert the approaching calamity, which everyone thought must be inevitable.

Spider at last said that possibly God would forgive them, if they gave him a sheep to take to Mendi.

“Sheep!” creid the people. “We will give you any number of sheep so long as you stop this trouble.”

Ananse was satisfied with ten sheep and he went his way.

He had no further adventures until he reached the outskirts of Mendi with his sheep. He was a little tired, however, and sat down outside the village and allowed his sheep to graze. He was still resting when there came toward him a company of people, wailing and weeping. They bore with them a corpse, and when Spider saluted them and asked what they were doing, they said that a young man had died and that they were now carrying him back to his village for burial.

Spider asked if the village was far, and they said it was far. Then he said that it was more than likely that the body would rot on the road, and they agreed. He then suggested that they should give him the corpse and in exchange he would give them the ten sheep. This was a novel kind of business deal, but it sounded all right and, after a little while, the company of young men agreed and they went off with the sheep, leaving their dead brother with Spider.

The latter waited until nightfall and then walked into town, carrying with him the corpse. He came to the house of the chief of Mendi and saluted that nighty monarch, and begged for a small place where he could rest. He added:

“I have with me as companion the son of God. He is his favorite son, and, although you know me as the captain of God’s Host, yet I am only as a slave to this boy. He is asleep now, and as he so tired I want to find a hut for him.”

This was excellent news for the people of Mendi and a hut was soon ready for the favorite son of God.

Spider placed the corpse inside and covered it with a cloth so that it seemed verily like a sleeping man. Spider then came outside and was given food. He feasted himself well and asked for some food for God’s son. This he took into the hut where, being greedy, he finished the meal and came out bearing with him the empty pots.

Now the people of Mendi asked if they might play and dance, for it was not often a son of God came to visit them. Spider said that they might, for he pointed out to them that the boy was an extraordinarily hard sleeper and practically nothing could wake him – that he himself, each morning, had had to flog the boy until he woke, and that shaking was no use, nor was shouting. So they played and they danced.

As the dawn came, Spider got up and said it was time for him and God’s son to be up and about their business. So he asked some of the chief”s own children who had been dancing to go in and wake the son of God. He said that, if the young man did not get up, they were to flog him, and then he would surely be aroused. The children did this, but God’s son did not wake. “Hit harder, hit harder! cried Spider, and the children did so. But still God’s son did not wake.

The Spider said that he would go inside and wake him himself. So he arose and went into the hut and called to God’s son. He shook him, and then he made the startling discovery that the boy was dead. Spider’s cries drew everyone to the door of the compound, and there they learned the dreadful news that the sons of their chief had beaten God’s favorite child to death.

Great was the consternation of the people. The chief himself came and saw and was convinced. He offered to have his children killed; he offered to kill himself; he offered everything imaginable. But Spider refused and said that he could think of nothing that day, as his grief was too great. Let the people bury the unfortunate boy and perhaps he, Spider would devise some plan by which God might be appeased.

So the people took the dead body and buried it.

That day all Mendi was silent, as all men were stricken with fear.

But in the evening Spider called the chief to him and said, “I will return to my father, God, and I will tell him how the young boy has died. But I will take all the blame on myself and I will hide you from his wrath. You must, however, give me a hundred young men to go back with me, so that they can bear witness as to the boy’s death.”

The the people were glad, and they chose a hundred of the best young men and made them ready for the long journey to the abode of God.

Next morning Spider arose and, finding the young men ready for the road, he went with them back to Wolof and from there he took them up to God.

The latter saw him coming with the crowd of youths and came out to greet him. And Spider told him all that he had done and showed how from one single corn cob God had now got a hundred excellent young slaves. So pleased was God that he confirmed Spider in his appointment as Chief of his Host and changed his name from Aphthis to Spider, which it has remained to the present day.

Now Spider got very conceited over this deed and used to boast greatly about this cleverness. One day he even went so far as to say that he possessed more sense than God himself. It happened that God overheard this, and he was naturally annoyed at such presumption. So, next day, he sent for his captain and told him that he must go and fetch him something. No further information was forthcoming, and Spider was left to find out for himself what God wanted.

All day Spider thought and thought, and in the evening God laughed at him and said, “You must bring me something. You boast everywhere that you are my equal, now prove it.”

So next day Spider arose and left the sky on his way to find something. Presently he had an idea and, sitting down by the wayside, he called all the birds together. From each one he borrowed a fine feather and then dismissed them. Rapidly he wove the feather into a magnificent garment and then returned to God’s town. There he put on the wonderful feather robe and climbed up the treed over against God’s house. Soon God came out and saw the garishly colored bird. It was a new bird to him, so he called all the people together and asked them the name of the wonderful bird. But none of them could tell, not even the elephant, who knows all that is in the far, far bush. Someone suggested that Spider might know, but God said that, unfortunately, he had sent him away on an errand. Everyone wanted to know the errand and God laughed and said, “Spider has been boasting too much and I heard him say that he has as much sense as I have. So I told him to go and get me something.” everyone wanted to know what this something was, and God explained that Spider would never guess what he meant, for the something he wanted was nothing less than the sun, the moon, and darkness.

The meeting then broke up amid roars of laughter at Spider’s predicament and God’s exceeding cleverness. But Spider, in his fine plumes, had heard what was required of him and, as soon as the road was clear, descended from his tree and made off to the bush.

There he discarded his feathers and went far, far away. No man knows quite where he went, but, wherever he went, he managed to find the sun and the moon and the darkness. Some say that the python gave them to him, others are not sure. In any case, find them he did and, putting them into his bag, he hastened back to God.

He arrived at his master’s house late one afternoon and was greeted by God who, after a while, asked Spider if he had brought back something.

“Yes,” said Spider, and went to his bag and drew out darkness. Then all was black and no one could see. Thereupon he drew out the moon and all could see a little again. The last he drew out the sun, and some who were looking at Spider saw the sun and they became blind, and some who saw only a little of it were blinded in one eye. Others, who had their eyes shut at the moment, were luckier, so they lost nothing of their eyesight.

Thus it came about that blindness was brought into the world, because God wanted something.

[ KRACHI ]