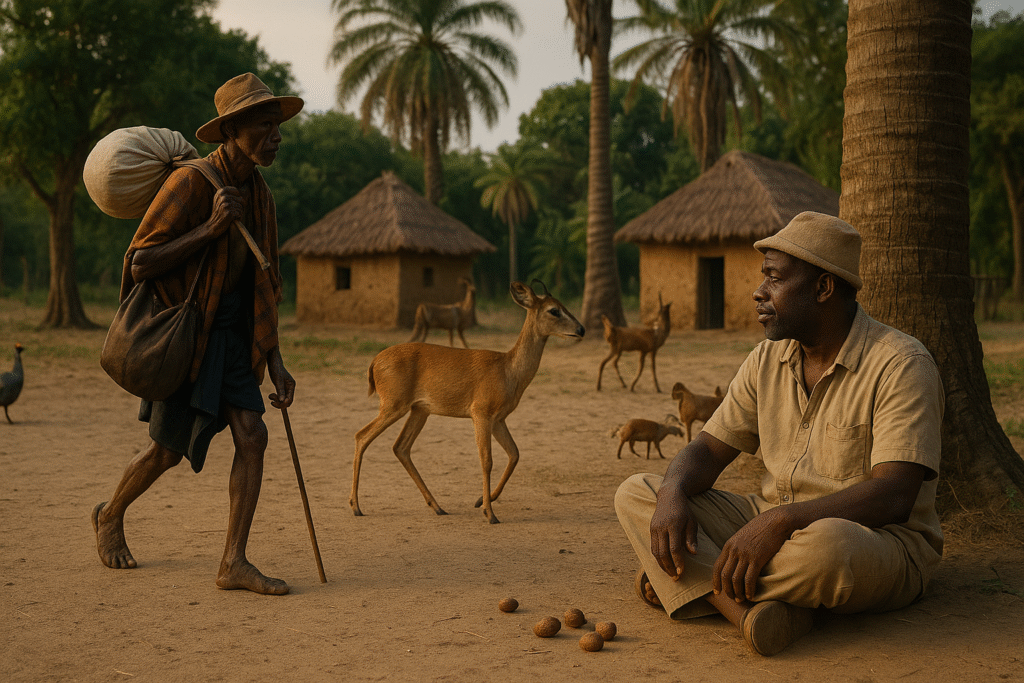

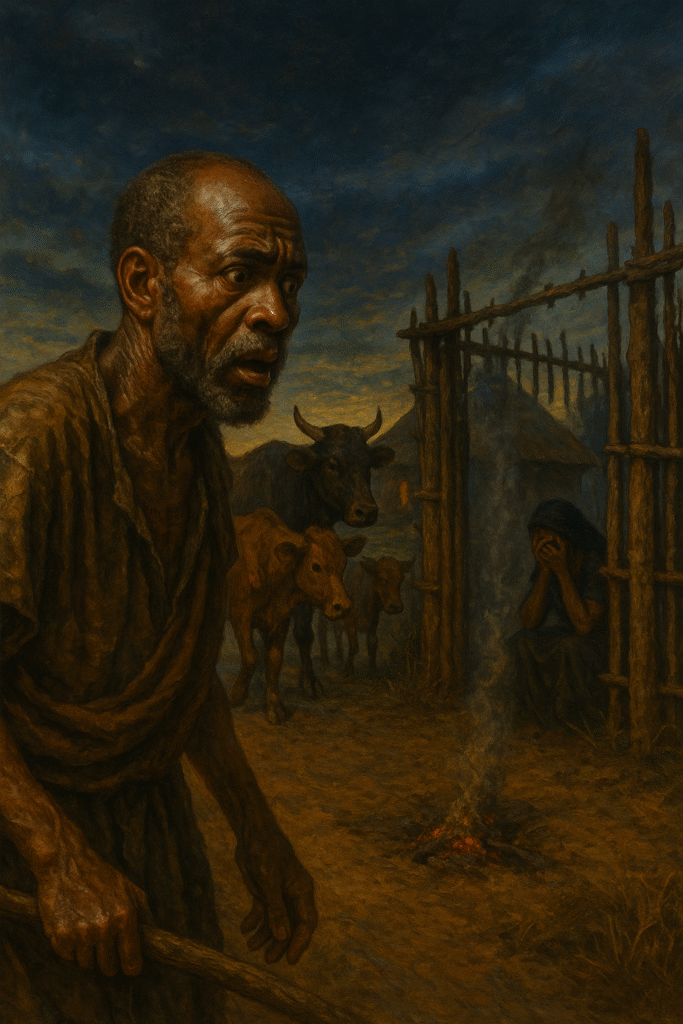

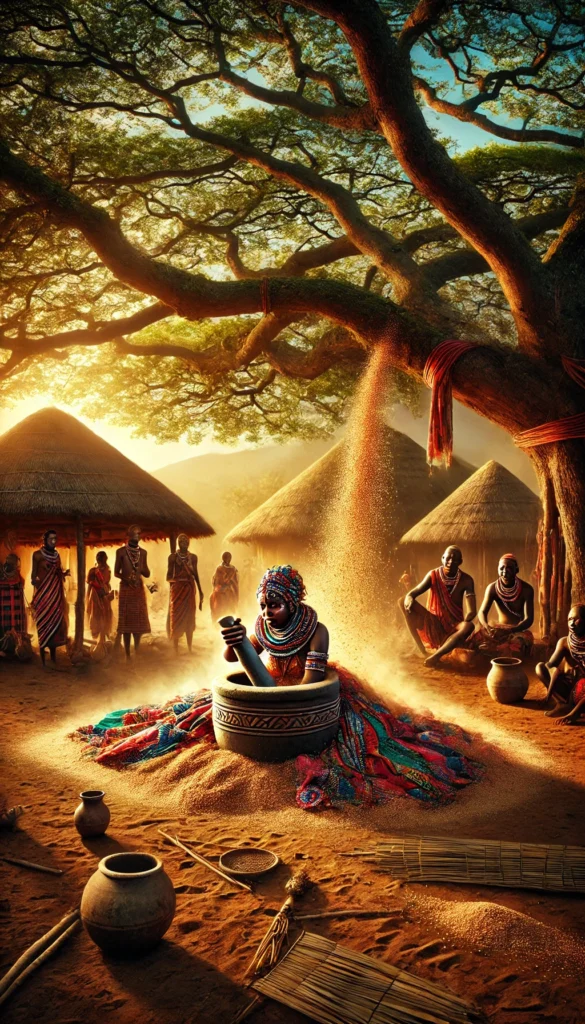

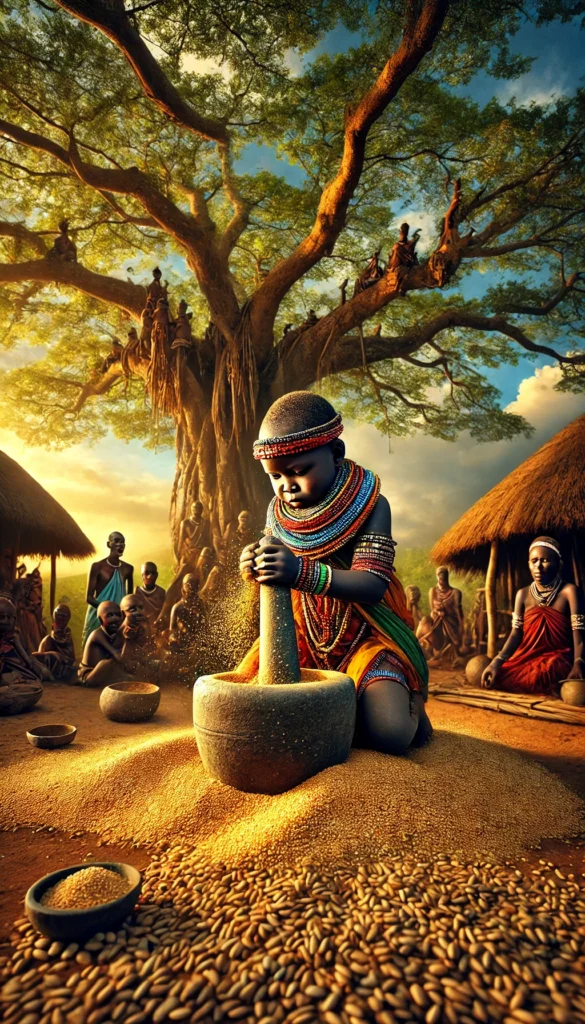

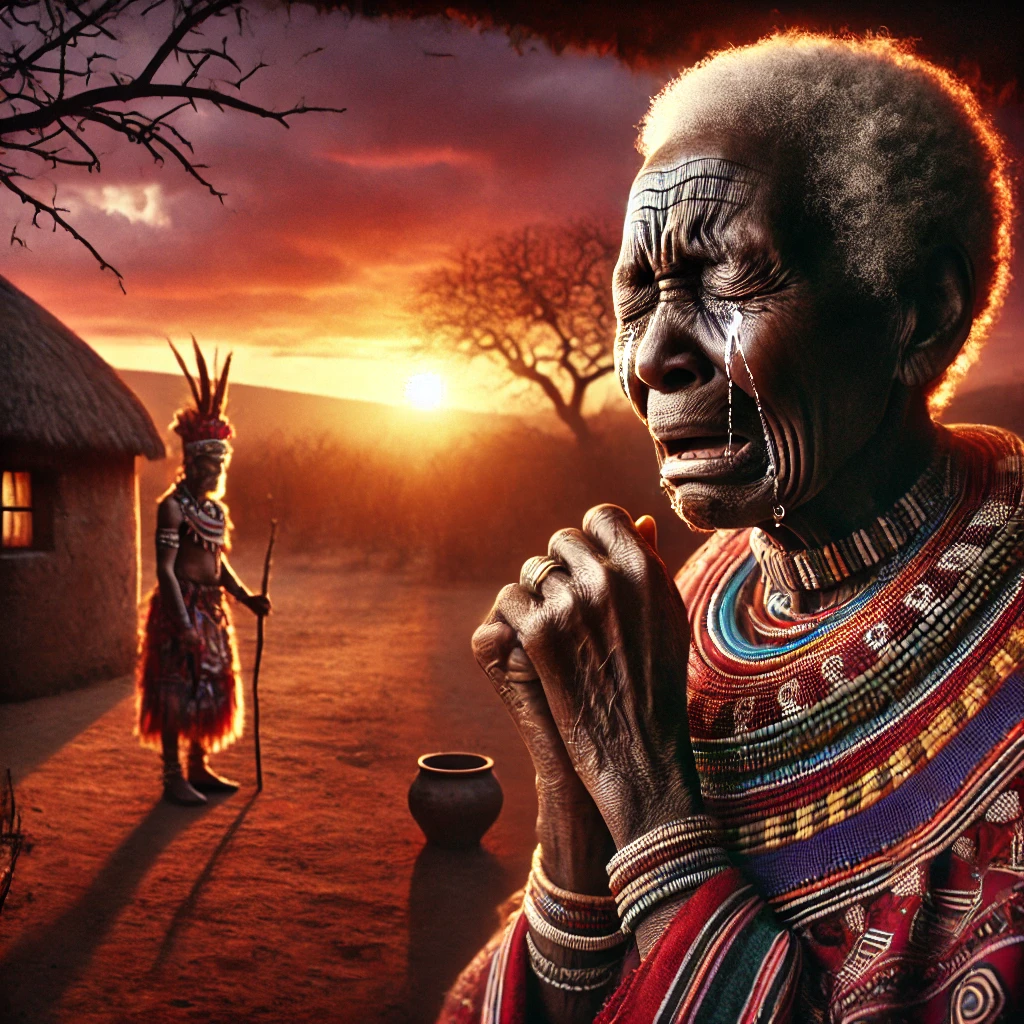

THEY SAY that once upon a time a great famine came, and the Father Spider, and his wife Wan, and his children, Diakhu, Mandara (Thin-Shanks), Kau Kau (Belly-Like-to-Burst), and Tikonokono (Big-Big-Head), built a little settlement and lived in it. Every day the spider used to go and bring food – wild yams – and they boiled and ate them.

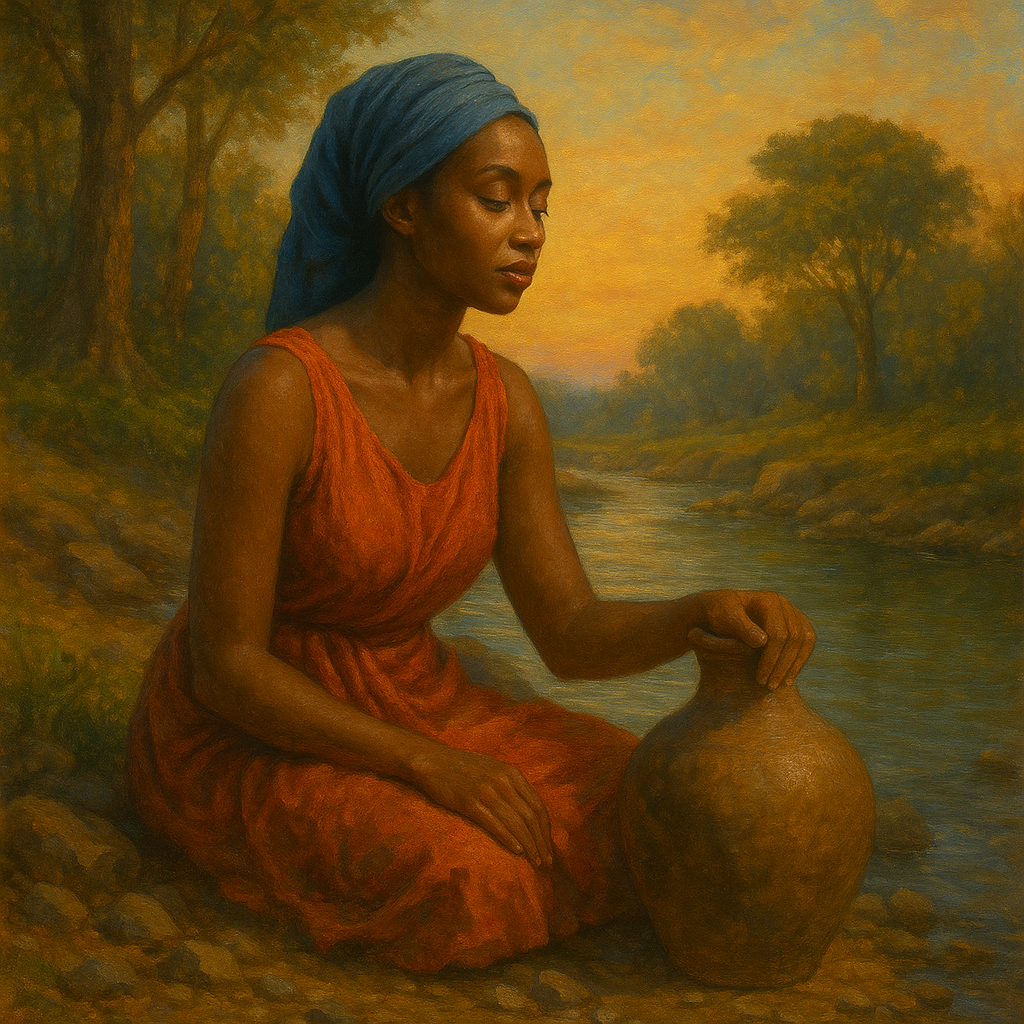

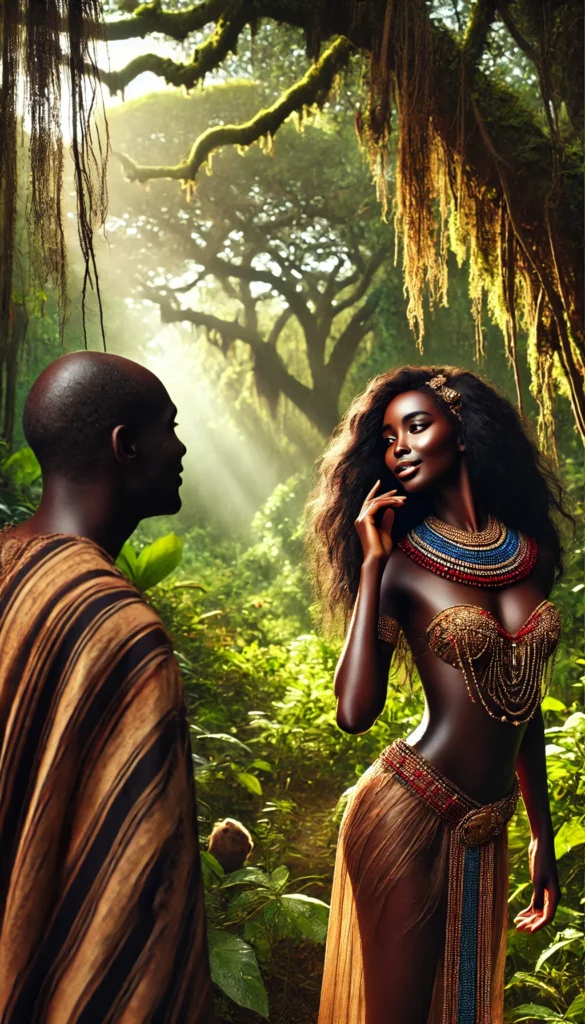

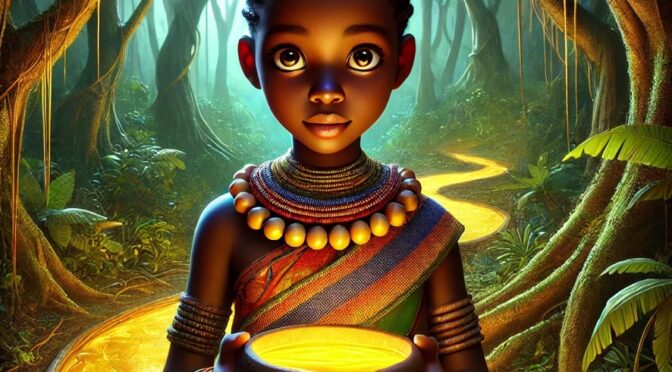

Now one day, father Spider went to the bush and he saw that a beautiful dish was standing there. He said, “This dish is beautiful.”

The dish said, “My name is not beautiful.”

The spider then asked, “What are you called?”

It replied, “I am called ‘Fill-Up-Some-and Eat.'”

The spider said, “Fill up some so that I may see.”

The dish filled up with palm-oil soup, and Spider ate it all.

When he had finished, he asked the dish, “What is your taboo?”

The dish replied, “I hate a gun wad and a little gourd cup.”

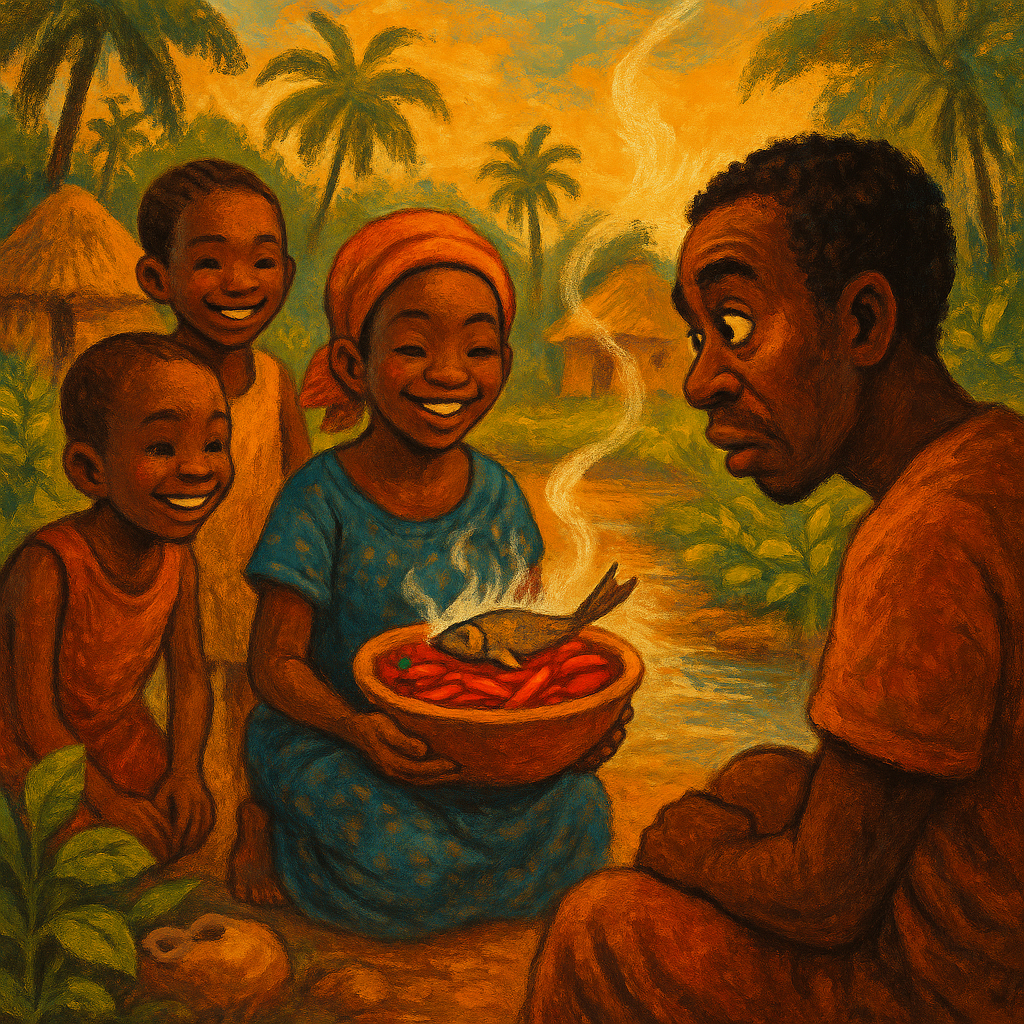

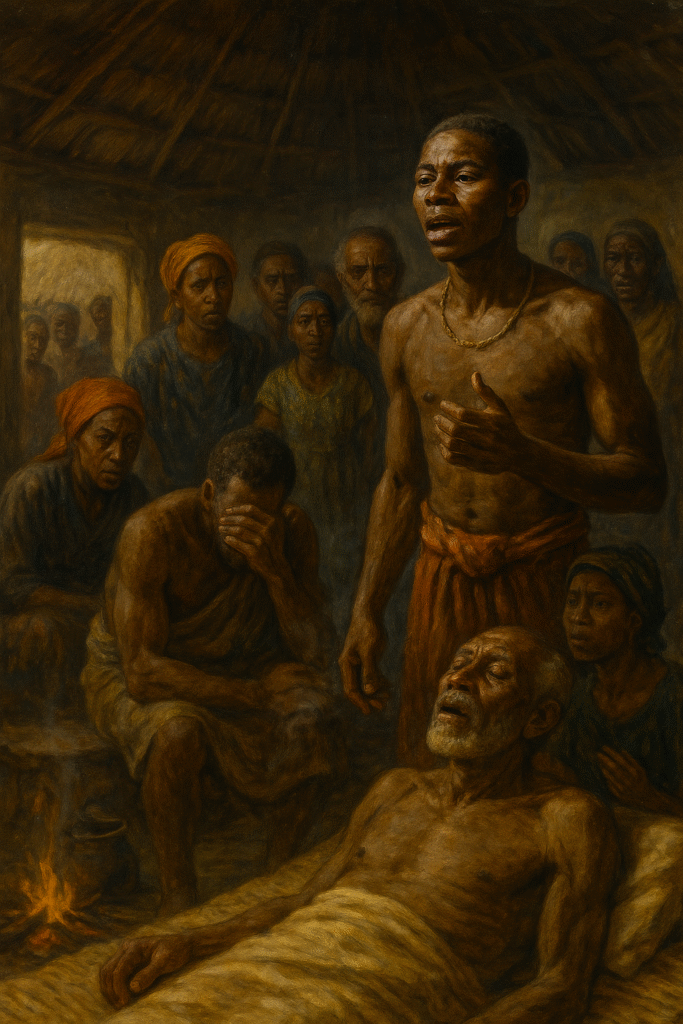

The spider took the dish home, and went and placed it on the ceiling. He went off to the bush and brought food, and Wan, when she had finished cooking, called Spider. He said, “Oh, yours is the real need. As for me, I am an old man. What should I have to do with food? You and these children are the ones in real need. If you are replete, then my ears will be spared the sounds of your lamentations.”

When they had finished eating, Spider passed behind the hut, and went and sat on the ceiling where the dish was. He said, “This dish is beautiful.”

It replied, “My name is not Beautiful.”

He said, “What is your name?”

He said, “I am called ‘Fill-Up-Some-and-Eat.'”

Spider said, “Fill up some for me to see.” And it filled up a plate full of ground-nut soup, and Spider ate. Every day when he arose it was thus.

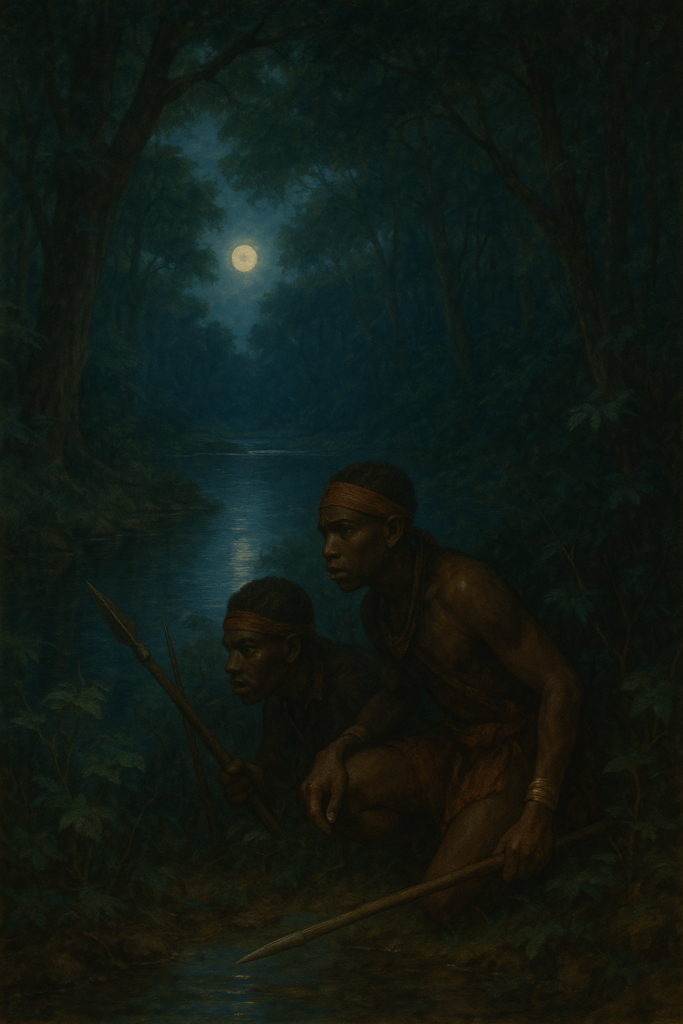

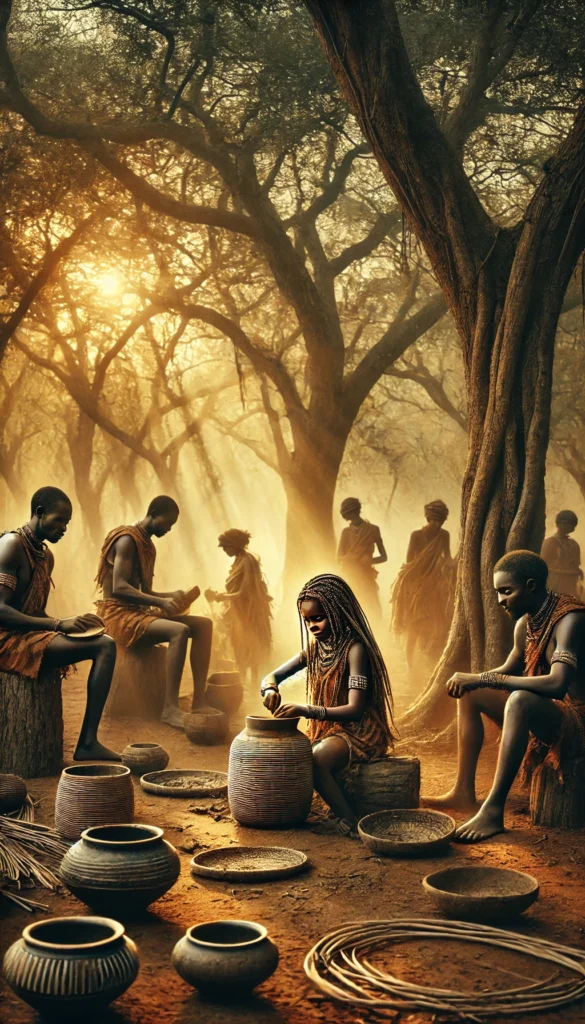

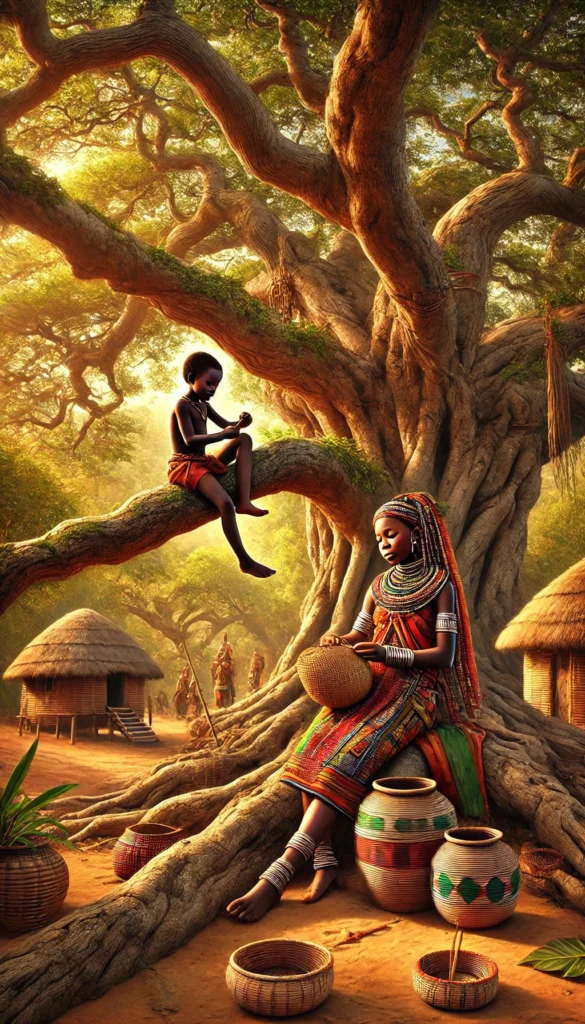

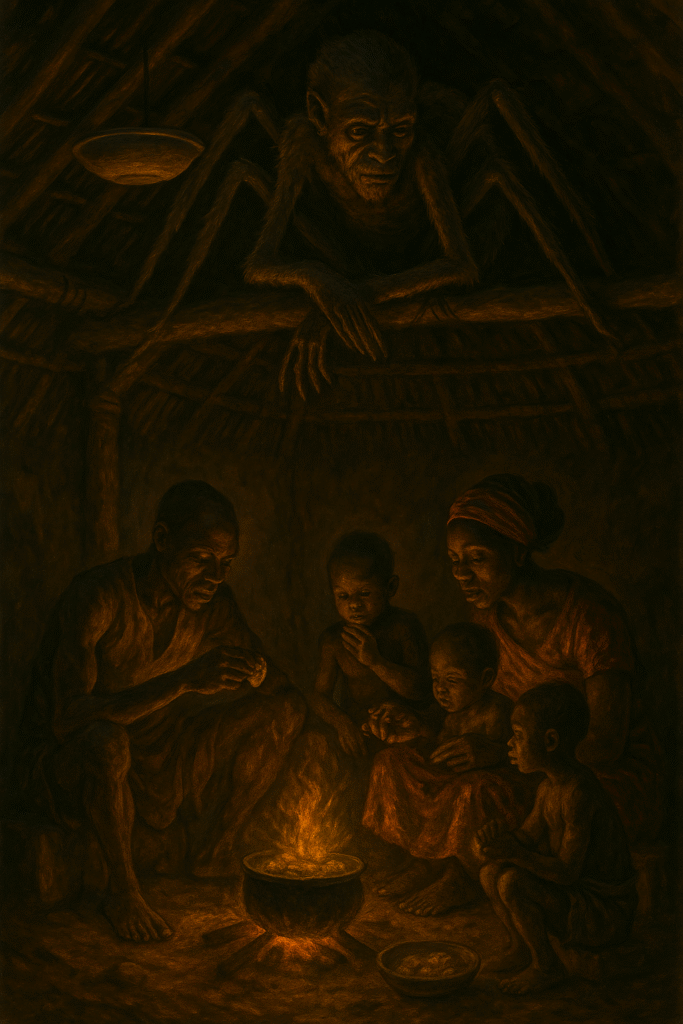

Now Mandara noticed that his father did not grow thin in spite of the fact that they and he did not eat together, and so he kept watch on his father to see what the latter had got hold of. When his father went off to the bush, Mandara climbed up on top of the ceiling and saw the dish. He called his mother and brothers and they, too went on top. Mandara said, “This dish is beautiful.”

It said, “I am not called ‘Beautiful.'”

He said, “Then what are you called?”

It said, “My name is ‘Fill-Up-Some-and-Eat.’ “

He said, “Fill up a little that I may see.” And the dish filled up to the brim with palm-oil soup.

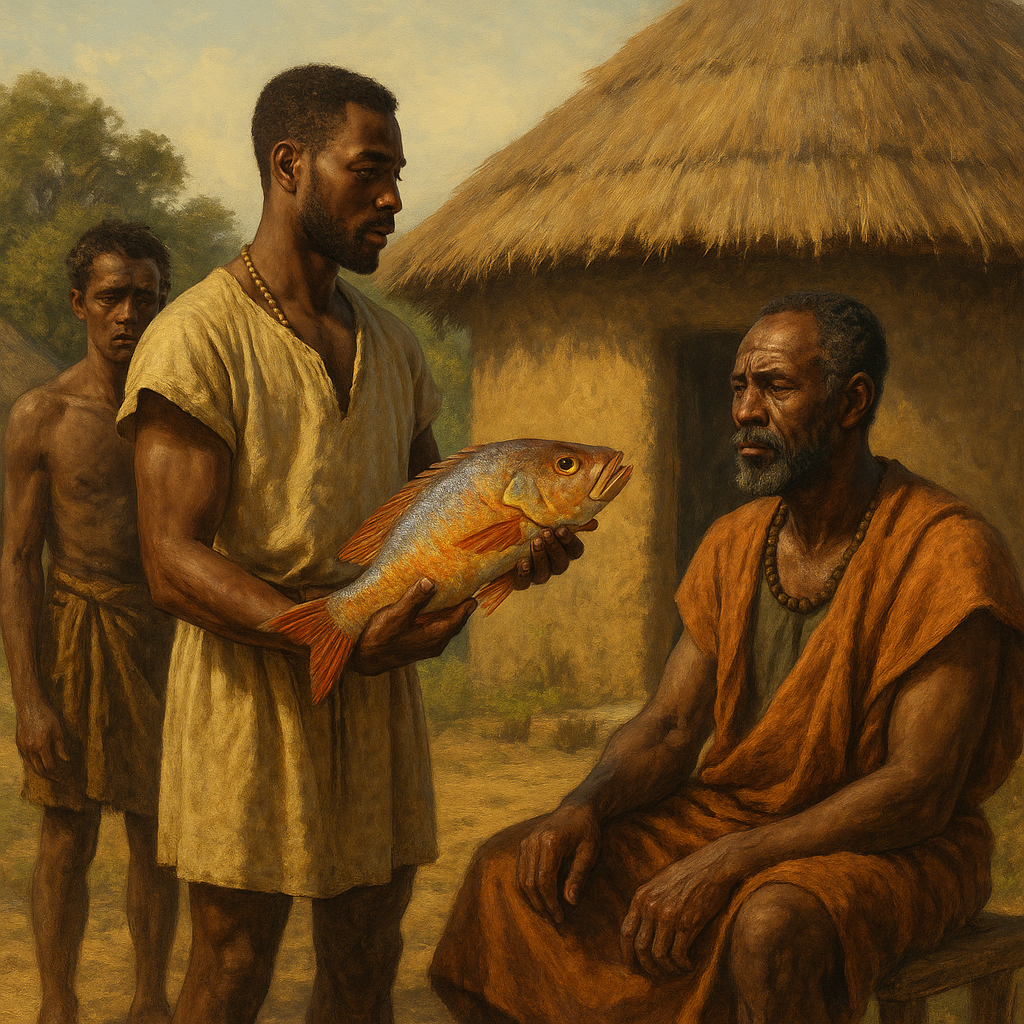

And now Diakhu asked the dish, “What do you taboo?”

The dish said, “I hate a gun wad and a small gourd cup.”

Diakhu said to Kau Kau, “Go and bring some for me.”

And he brought them, and Diakhu took the gun wad and touched the dish and also the little gourd cup and touched the dish with it. Then they all descended.

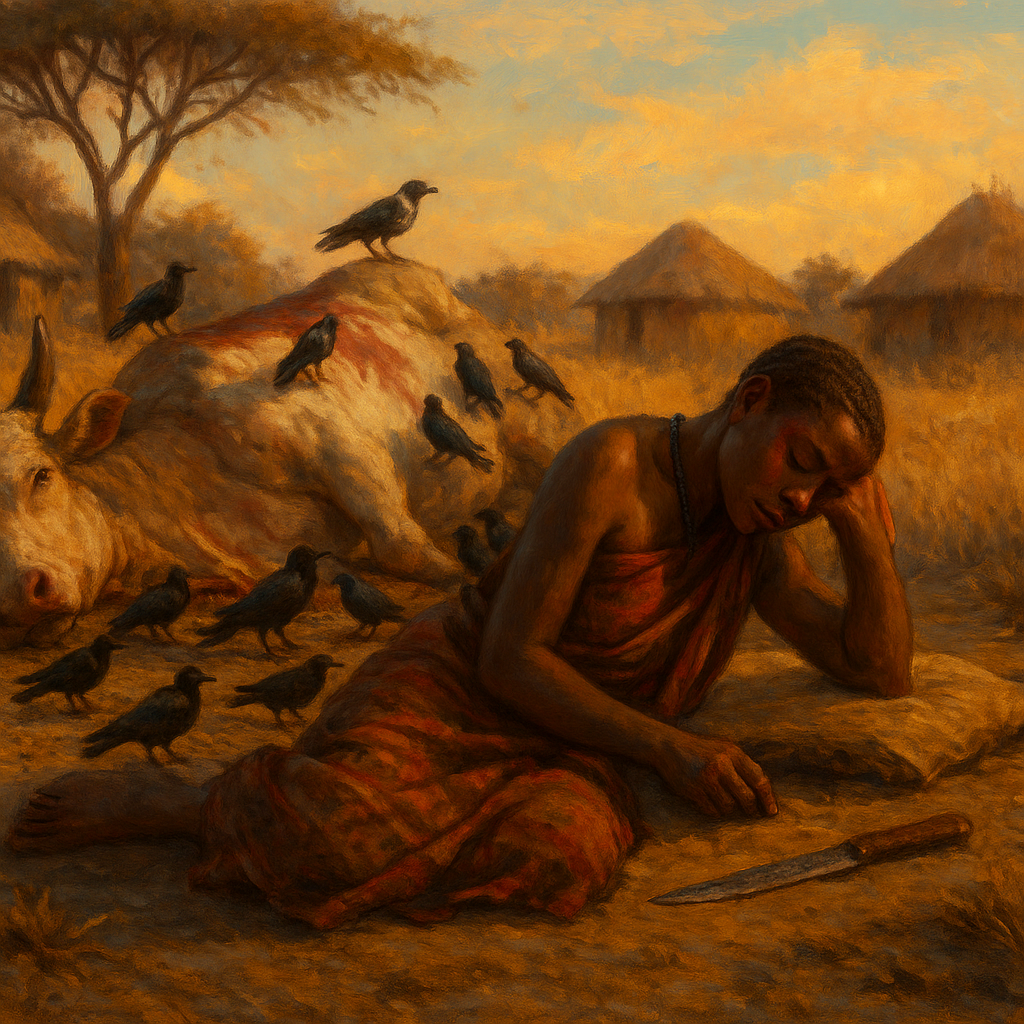

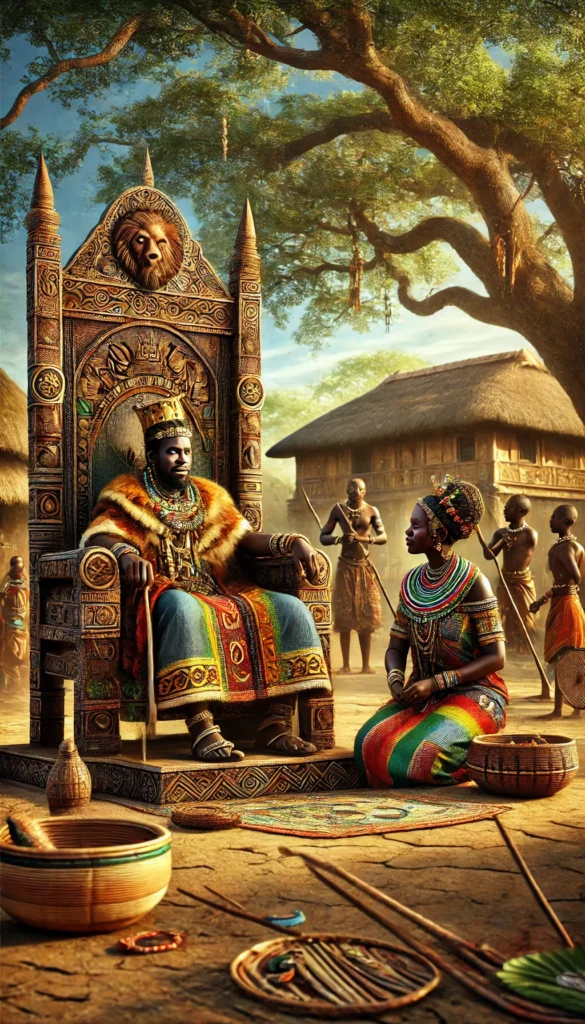

Father Spider mean time had come back from the bush with the wild yams. Wan finished cooking them. They called Spider.

He replied, “Perhaps you didn’t hear what I said – I said that when I come home with food, you may partake, for you are the ones in need.” Wan and her children ate.

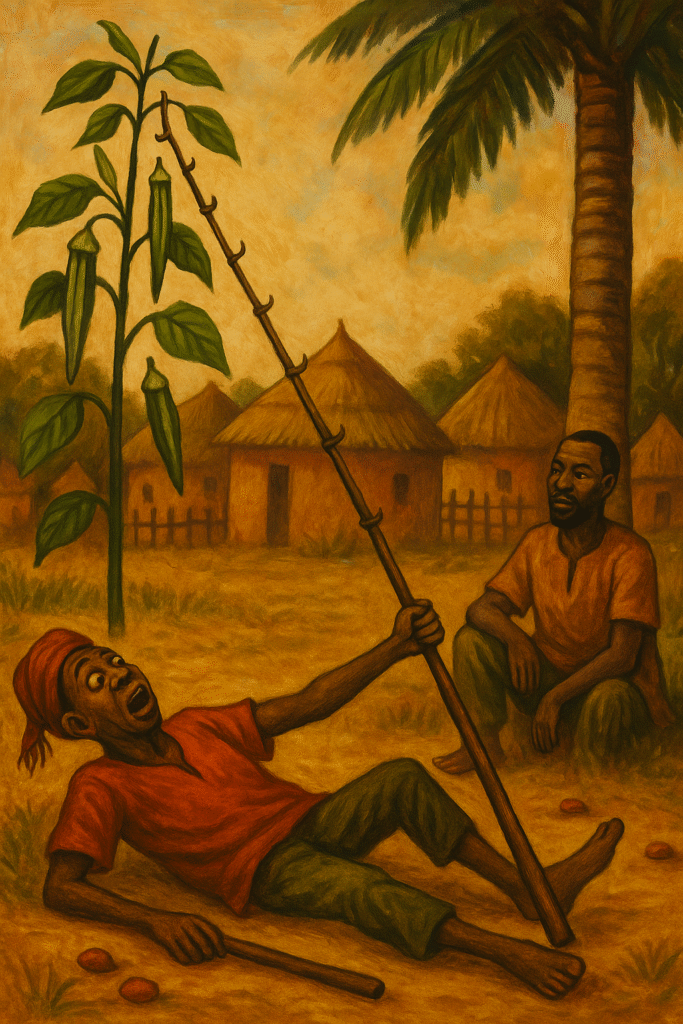

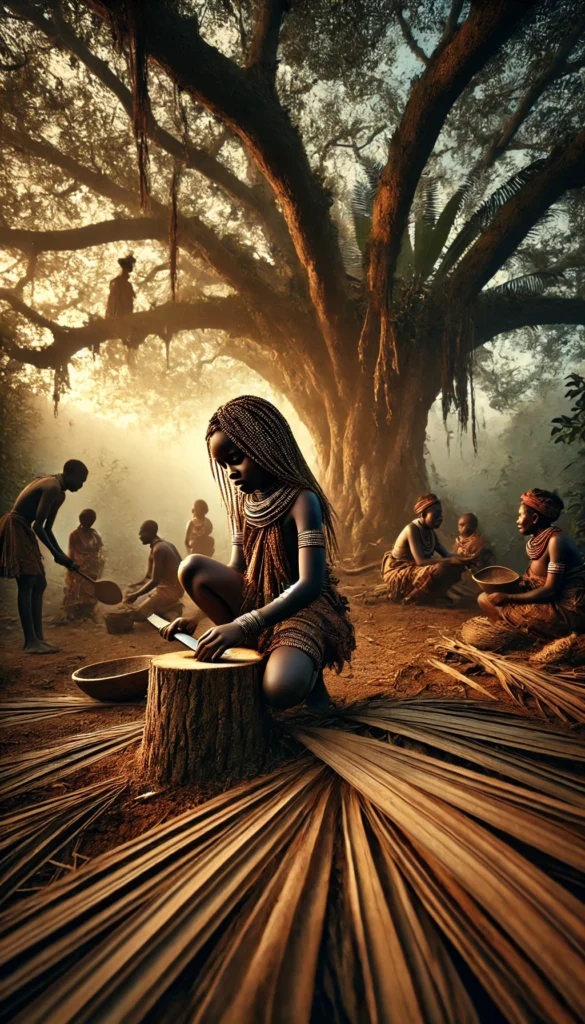

Father Spider washed and then climbed up on the ceiling. He said, “This dish is beautiful.” Complete silence! “This dish is beautiful!” Complete silence! Father Spider, “Ah! It must be on account of this cloth not being a beautiful one; I shall go and bring the one with the pattern of the Oyo clan and put it on.” And he descended to go and fetch the Oyo-pattern cloth to wear. He put on his sandals and again climbed up on the ceiling. He said, “This dish is beautiful.” Complete silence! “This dish is beautiful.” Complete silence! He looked round the room and saw that a gun wad and a little gourd cup were there.

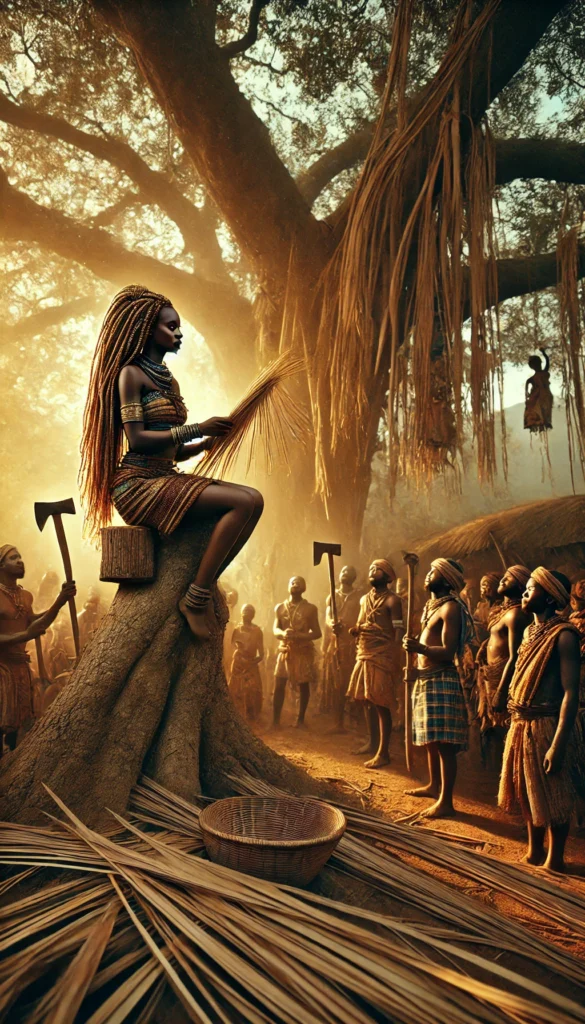

Spider said, “It’s not one thing, it’s not two things – it’s Diakhu.” Spider smashed the dish, and came down. He took off the Oyo-pattern cloth, laid it away, and went off to the bush. As he was going, he saw that a very beautiful thing called Mpere, the whip, was hanging there. He said, “Oh, wonderful! This thing is more beautiful than the last. This whip is beautiful.”

The whip said, “I am not called Beautiful.’ “

The spider said, “Then what are you called?”

It said, “I am called ‘Abiridiabrada,’ or ‘Swish-and-Raise-Welts.’ “

And spider said, “Swish a little for me to see.” And the whip fell upon him biridi, biridi, biridi! Father Spider cried, “Pui! pui!’

A certain bird sitting nearby said Spider Say ‘Adwobere, cool-and-easy-now.’ “

And Spider said, “Adwobere, cool-and-easy-now.”

And the whip stopped beating him. And Spider brought this whip home; and he went and placed it on the ceiling.

Wan finished cooking the food and said, “Spider, come and eat.”

He replied, “Since you are still here on earth, perhaps you have not a hole in your ears and don’t hear what I had said – I shall not eat.” Spider climbed up above and went and sat down quietly. Soon he came down again and he went and hid himself somewhere.

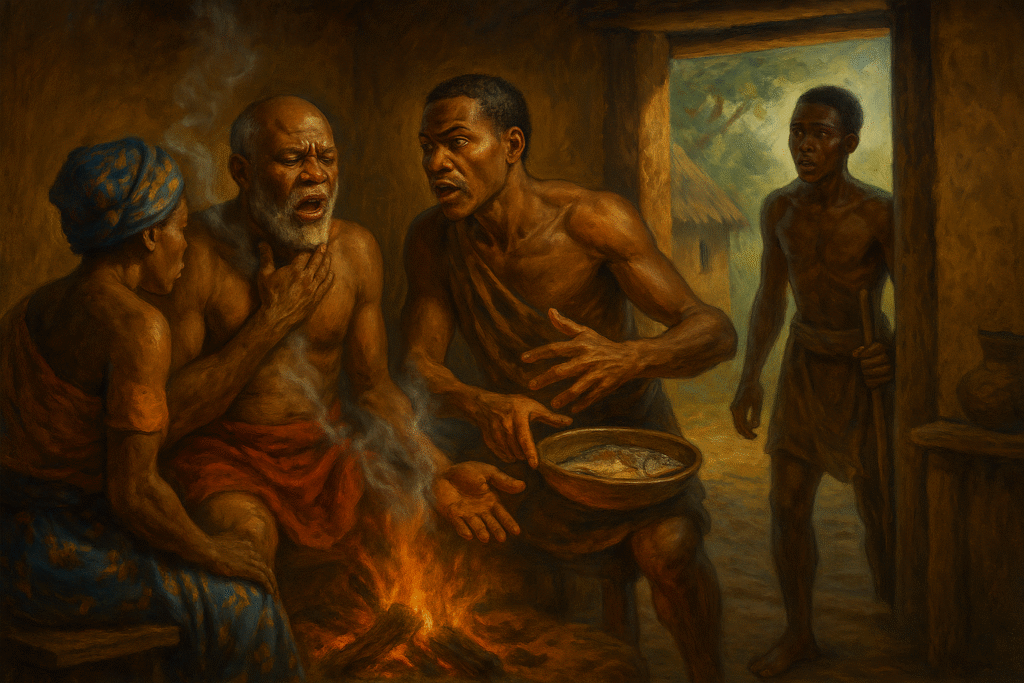

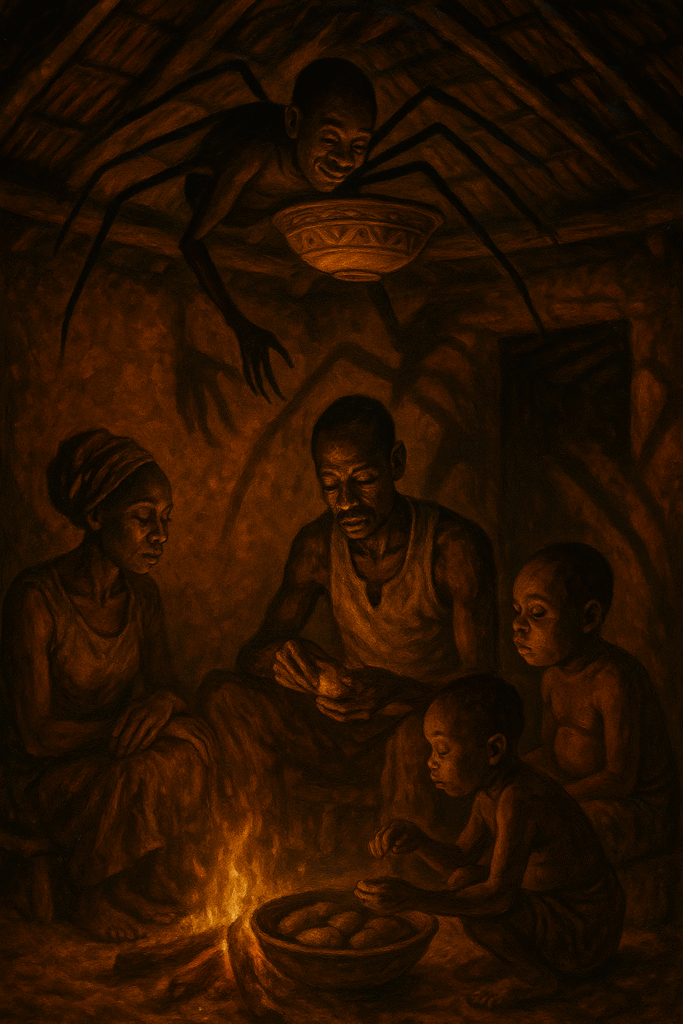

Then Diakhu climbed up aloft. He said, “Oh, that father of mine has brought something home again!” Diakhu called, “Mother, Mandara, Kau Kau, come here, for the thing father has brought this time excels the last one by far!” Then all of them climbed up on the ceiling. Diakhu said, “This thing is beautiful.”

It replied, “I am not called ‘Beautiful.’ “

He said, “What is your name?”

It said, “I am called ‘Swish-and-Raise-Welts.’ “

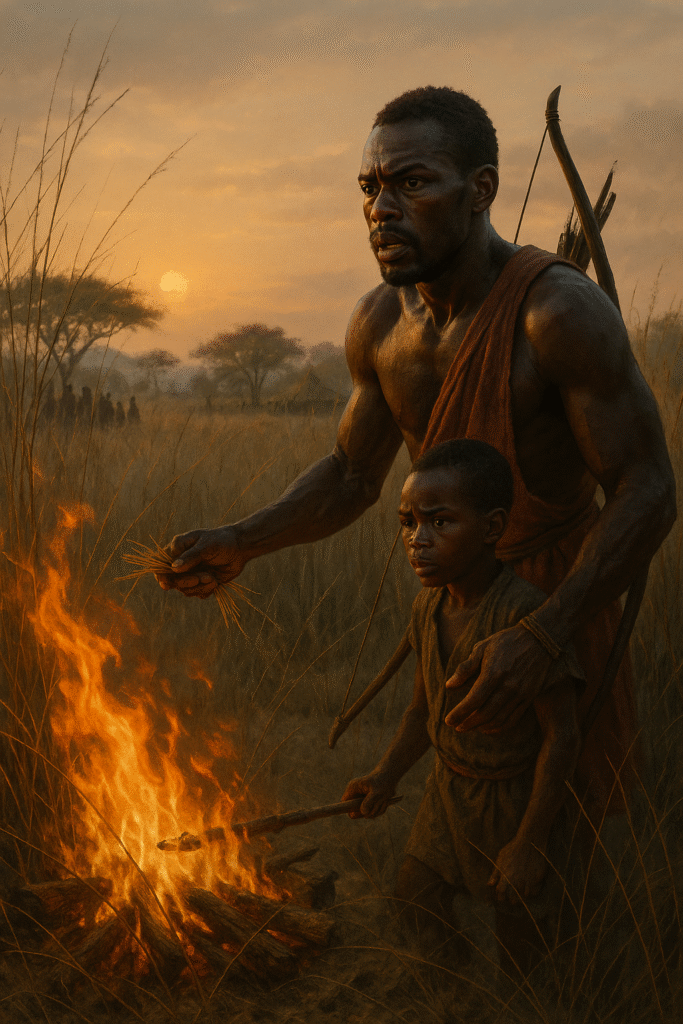

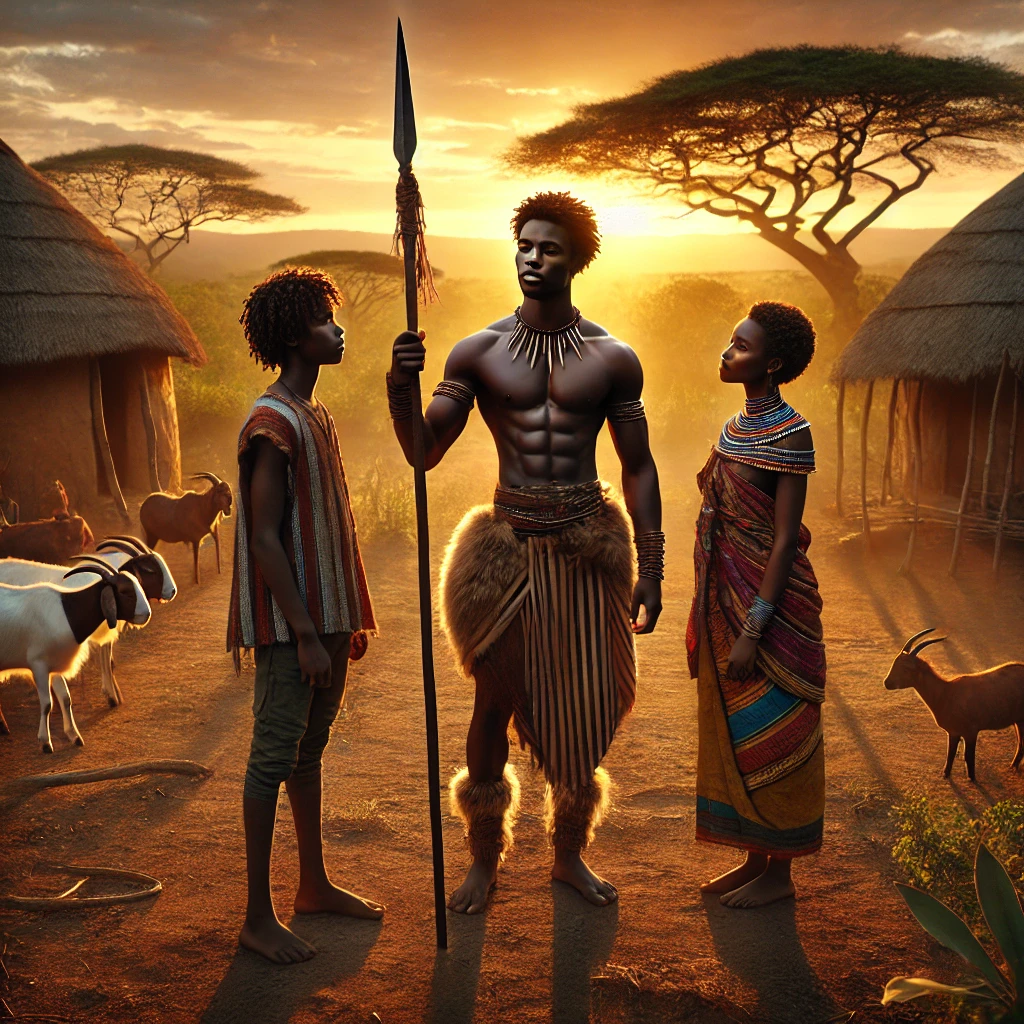

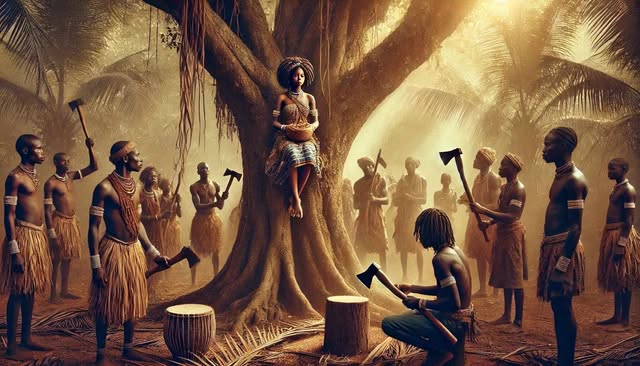

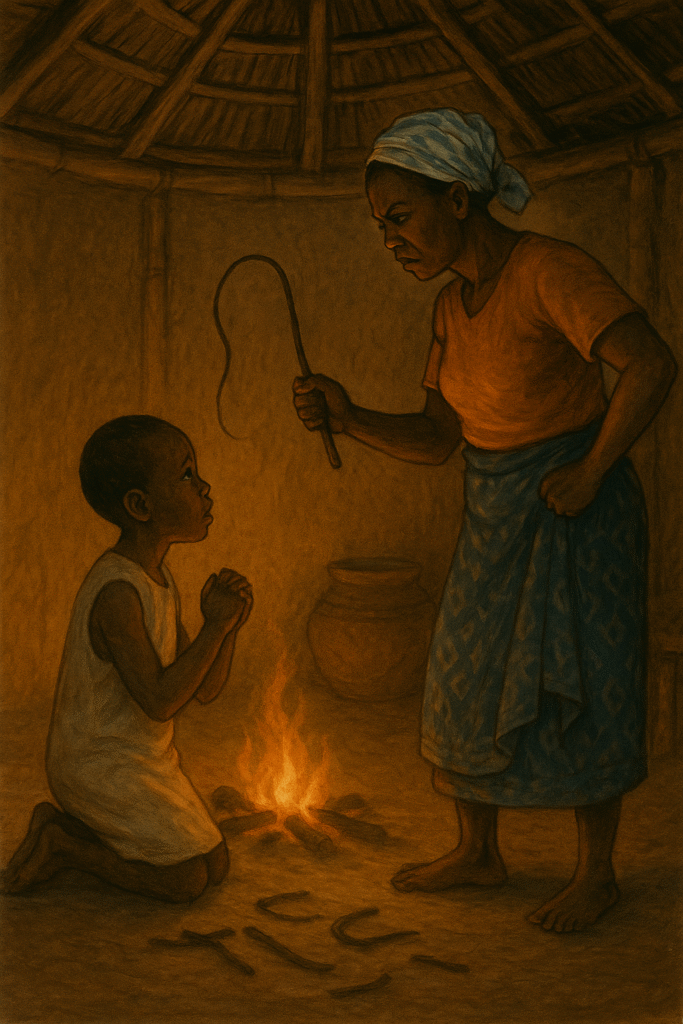

He said, “Swish a little for me to see.” And the whip descended upon them and flogged them severely.

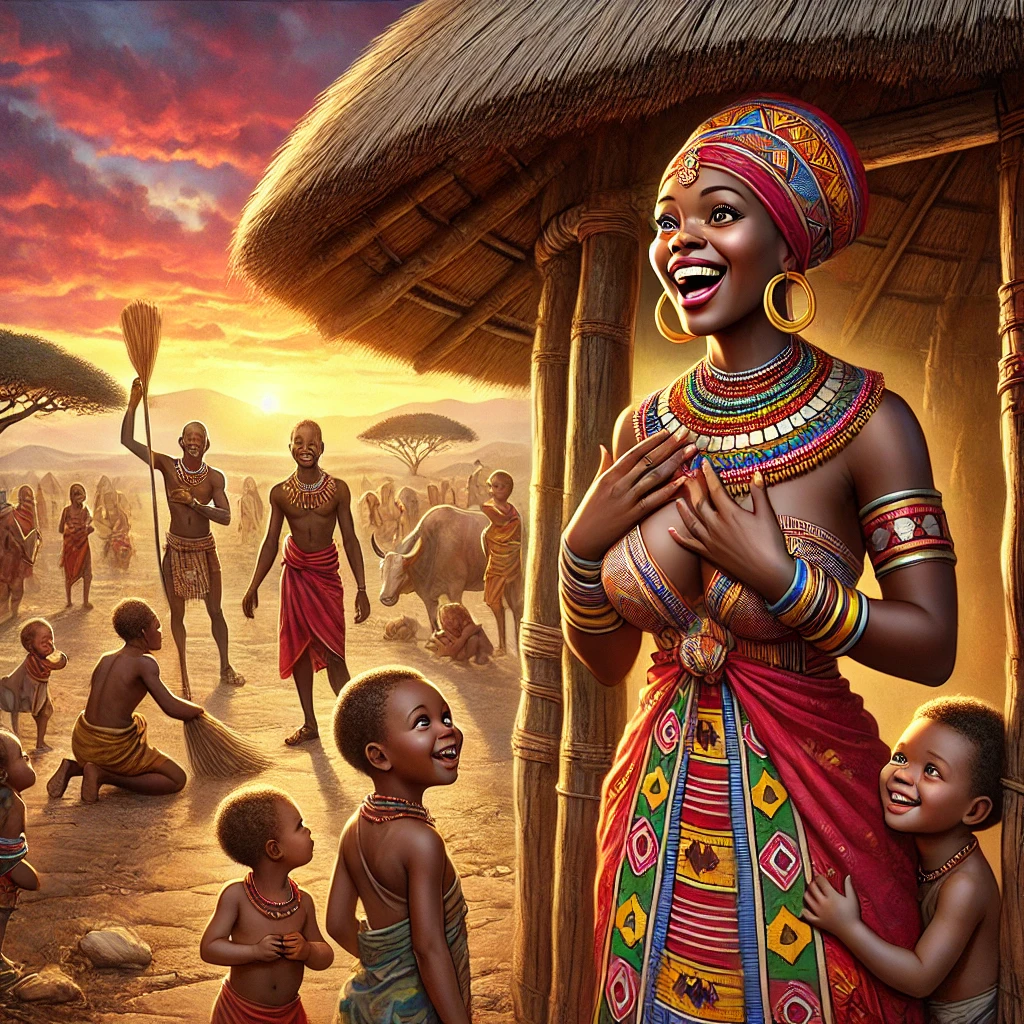

Spider stood aside and shouted, “Lay it on, lay it one! Especially on Diakhu, lay it on him!” Now when Spider has watched and seen that they were properly flogged, he said, “Adwobere, cool-and-easy-now.” Spider came and took the whip and cut it into pieces and scattered them about.

That is what made the whip come into the tribe. So it comes about that when you tell your child something and he will not listen to you, you whip him.

[ ASHANTI }