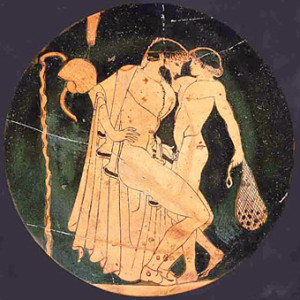

It is almost commonplace to say that those who are in love can converse without words. Dramas and stories of all kinds have been written about the inner kind of communication that seems to take place between mother and children, sister and brother, or love and beloved.

Love itself seems to quicken the physical senses, so that even the most minute gestures attain additional significance and meaning. Myths and tales are formed in which those who love communicate, though one is dead while the other lives. The experience of love also deepens the joy of the moment, even while it seems to emphasize the briefness or morality. Though love’s expression brilliantly illuminates its instant, at the same time that momentary brilliance contains within it an intensity that defies time, and is somehow eternal.

In our world we identify as oneself only, and yet love can expand that identification to such an extent that the intimate awareness of another individual is often a significant portion of our own consciousness. We look outward at the world not only through our eyes, but also, to some extent at least, through the eyes of another. It is true to say, then, that a portion of us figuratively walks with this other person as he or she goes about separate from us in space.

All of this also applies to the animals to varying degrees. Even in animals groups, individuals are not concerned with personal survival, but with the survival of “family” members. Each individual in an animal group is aware of others’ situations. The expression of love is not confined to our own species, therefore, nor is tenderness, loyalty, or concern. Love indeed does have its own language — a basic nonverbal one with deep biological connotations. It is the initial basic language from which all others spring, for all languages’ purposes rise from those qualities natural to love’ expression — the desire to communicate, create, explore, and to join with the beloved. If you want to express your love for someone but you’re not sure what to say, search for inspirational-love-quotes-sayings, look at this site for some ideas.

Speaking historically in our terms, man and woman first identified with nature, and loved it, for he/she saw it as an extension of himself or herself even while he or she felt himself or herself a part of its expression. In exploring it he/she explored love, he/she identified also with all those portions of nature with which he/she came into contact. This love was biologically ingrained in him or her, and is even now biologically pertinent.

Physically and psychically the species is connected with all of nature. Man and woman did not live in fear, as is now supposed, nor in some idealized natural heaven. He/she lived at an intense peak of psychic and biological experience, and enjoyed a sense of creative excitement that in those terms only existed when the species was new.

Difficult to explain, for these concepts themselves exist beyond verbalization. Some seeming contradictions are bound to occur. In comparison with those times, however, children are now born ancient, for even biologically they carry with in themselves the memories of their ancestors. In those pristine ears, however, the species itself arose, in those terms, newly from the womb of timelessness into time.

In deeper terms their existence still continues, with offshoots in all directions. The world that we know is one development in time, the one that we recognize. The species actually took many other routes unknown to us, unrecorded in our history fresh creativity still emerges at that “point.” In the reckoning that we accept, the species in its infancy obviously experienced selfhood in different terms from our own. Because this experience is so alien to our present concepts, and because it predated language as we understand it, it is most difficult to describe.

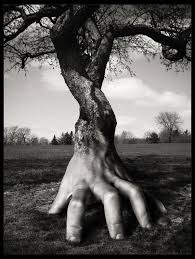

Generally we experience the self as isolate from nature, and primarily enclosed within our skin. Early man/woman did not feel like an empty shell, and yet selfhood existed for him/her as much outside of the body as within it. There was a constant interaction. It is easy to say that such people could identify, say, with the trees, but an entirely different thing to try and explain what it would be like for a mother to become so a part of the tree underneath which her children played that she could keep track of them from the tree’s viewpoint, though she was herself far away.