These, however, do not have to be trained to a particular space-time orientation.

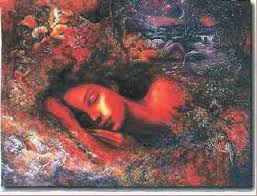

When children dream, they utilize these inner senses as adults do, and then through dreaming they learn to translate such material into the precise framework of the exterior senses. Children’s games are always “in the present” — that is, they are immediately experienced, though the play events may involve the future or the past. The phrase “once upon a time” is strongly evocative and moving, even to adults, because children play with time in a way that adults have forgotten. If we want to sense the motion of our psyche, it is perhaps easiest to imagine a situation either in the past or the future, for this automatically moves our mental sense-perceptions in a new way. Children try to imagine what the world was like before they entered it. Do the same thing. The way you follow these directions can be illuminating, for the areas of activity we choose will tell us something about the unique qualities of our own consciousness. Adult games deal largely with manipulations in space, while children’s play, again, often involves variations in time. Look at a natural object, say a tree; if it is spring now, then imagine that we see it in the fall.

Alter your time orientation in other such exercises. This will automatically allow you to break away from too narrow a focus. It will to some extent break apart the rigid interlocking of your perception into reality as we have learned how to perceive it. Children can play so vividly that they might, for example, imagine themselves parched under a desert sun, though they are in the middle of the coolest air-conditioned living room. They are on the one hand completely involved in their activity, yet on the other hand they are quite aware of their “normal” environment. Yet the adult often fears that any such playful unofficial alteration of consciousness is dangerous, and becomes worried that the imagined situation will supersede the real one.

Through training, many adults have been taught that the imagination itself is suspicious. Such attitudes not only drastically impede any artistic creativity, but the imaginative creativity necessary to deal with the nature of physical events themselves.

Man’s or woman’s creative alertness, his or her precise sensual focus in space and time, and his or her ability to react quickly to events, are of course all highly important characteristics. His or her imagination allowed him or her to develop the use of tools, and gave birth to his or her inventiveness. That imagination allows him or her to plan in the present for what might occur in the future.

This means that to some extent the imagination must operate outside of the senses’ precise orientation. For that reason, it is most freely used in the dream state. Basically speaking, imagination cannot be tied to practicalities, for when it is man or woman has only physical feedback. If that were all, then there would be no inventions. There is always additional information available other than that in the physical environment.

These additional data come as a result of the brain’s high play as it experiments with the formation of events, using the inner senses that are not structured in time or space.

Put another time on. Just before you sleep, see yourself as you are, but living in a past or future century — or simply pretend that you were born 10 or 20 years earlier or later. Done playfully, such exercises will allow you a good subjective feel for your own inner existence as it is a part from the time context.

To encourage creativity, exert your imagination through breaking up your usual space-time focus. As you fall to sleep, imagine that you are in the same place, exactly in the same spot, but at some point in the distant past or future. What do you see, or hear? What is there?

For another exercise, imagine that you are in another part of the world entirely, but in present time, and ask yourself the same questions. For variety, in your mind’s eye follow your own activities of the previous day. Place your self a week ahead in time. Conduct your own variations of these exercises. What they will teach you cannot be explained, for they will provide a dimension of experience, a feeling about your self that may make sense only to you.

They will teach us to find our own sensation of oneself, as divorced from the official context of reality, in which we usually perceive our being. Additionally, we will be better able to deal with current events, for our exercised imagination will bring information to us that will be increasingly valuable.

Do not begin by using your imagination only to solve current problems, for you will tie your creativity to them, and hamper it because of your beliefs about what is practical.

Playfully done, these exercises will set into action other creative events. These will involve the utilization of some of the inner senses, for which we have no objective sense-correlations. We will understand situations better in daily life, because we will have activated inner abilities that allow us to subjectively perceive the reality of other people in away that children do.

There is an inner knack, allowing for greater sensitivity to the feelings of others than we presently acknowledge. That knack will be activated. Again, the powers of the brain come from the mind, so while we learn to center our consciousness in our body — and necessarily so — nevertheless our inner perceptions roam a far greater range. Before sleep, then, imagine your consciousness traveling down a road, or across the world — whatever you want. Forget you body. Do not try to leave it for this exercise. Tell yourself that you are imaginatively traveling.

If you have chosen a familiar destination, then imagine the houses you might pass. It is sometimes easier to choose an unfamiliar location, however, for then we are not tempted to test yourself as you go along by wondering whether or not the imagined scenes conform to your memory.

To one extent or another your consciousness will indeed be traveling. Again, a playful attitude is best. If you retain it, and remember children’s games then the affair will be entirely enjoyable; and even if you experience events that seem frightening, you will recognize them as belonging to the same category as the frightening events of a child’s game.

Children often scare themselves. A variety of reasons exist for such behavior. People often choose to watch horror films for the same reason. Usually the body and mind are bored, and actually seek out dramatic stress. Under usual conditions the body is restored — flushed out, so to speak — through the release of hormones that have been withheld, often through repressive habits.

The body will seek its release, and so will the mind. Dreams, or even daydreams of a frightening nature, can fulfill that purpose. The mind’s creative play often serves up symbolic events that result in therapeutic physical reactions, and also function as post-dream suggestions that offer hints as to remedial action.

I mention this here simply to point out the similarity between some dreams and some children’s games, and to show that all dreams and all games are inherently involved with the creation and experience of events.