THE DAUGHTER OF THE KING Usikulumi said, “Father, I am going to the Llulange next year.” Her father said, “Nothing goes to that place and comes back again: it goes there for ever.” She came again the next year and said, “Father, I am going to the Llulange. Mother, I am going to the Llulange.” He said, “nothing goes to that place and comes back again: it goes there for ever.” Another year came round. She said, “Father, I am going to the Llulange.” She said, “Mother, I am going to the Llulange.” They said, “To the Llulange nothing goes and returns again: it goes there for ever.” The father and mother at last consented to let Untombinde go.

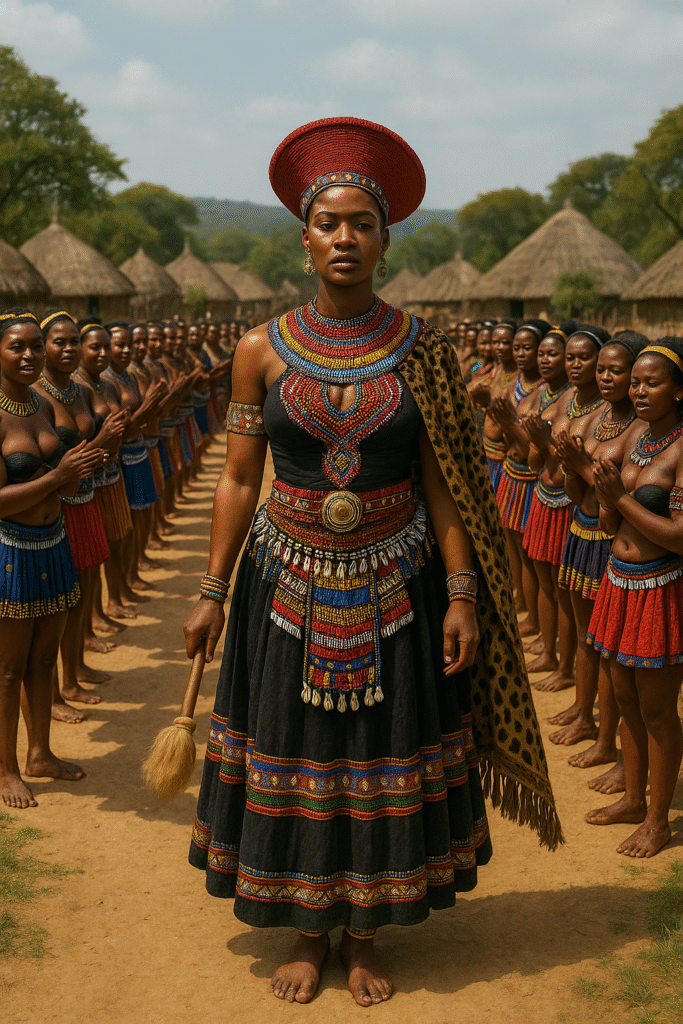

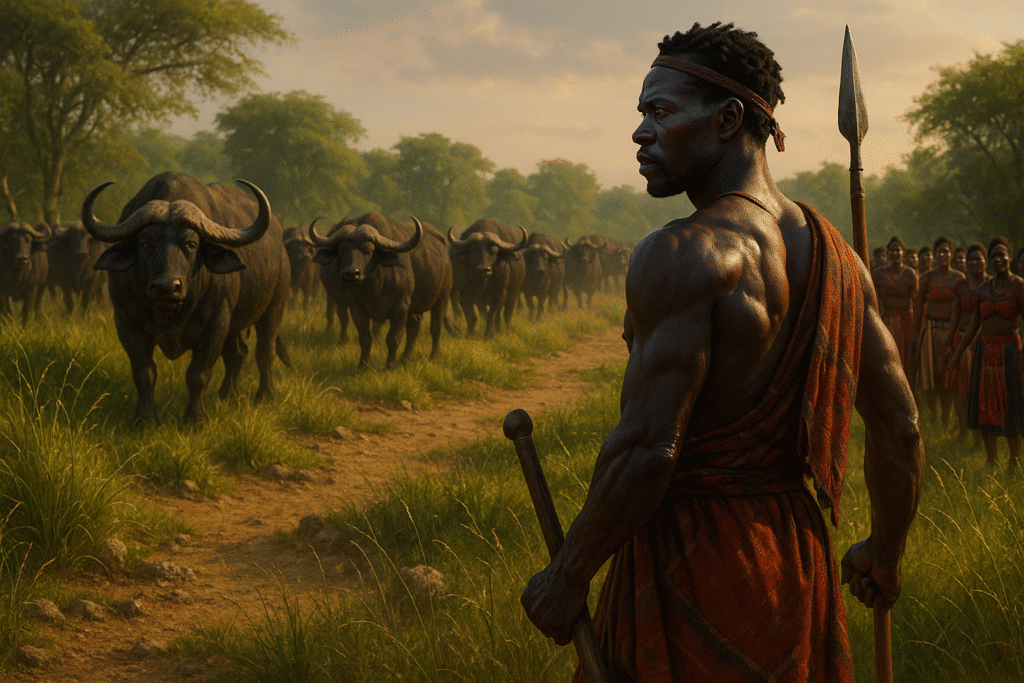

She collected a hundred virgins on one side of the road, and a hundred on the other. So they went on their way. They met some merchants. The girls came and stood on each side of the path, on this side and that. They said, “Merchants, tell us which is the prettiest girl here; for we are two wedding companies.” The merchants said, “You are beautiful, Utinkabazana; but you are not equal to Untombinde, the king’s child, who is like a spread-out surface of good green grass; who is like fat for cooking; who is like a goat’s gall-bladder!” The marriage company of Utinkabazana killed these merchants.

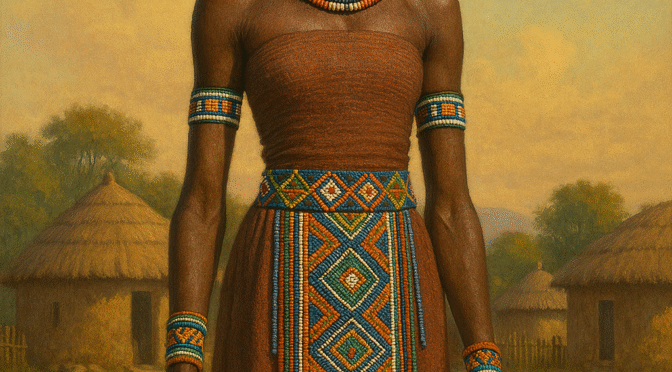

They arrived at the river Llulange. They had put on bracelets and ornaments for the breast, and collars, and petticoats ornamented with brass beads. They took them off, and placed them on the banks of the pool of the Llulange. They went in, and both marriage companies sported in the water. When they had sported a while, a little girl went out first and found nothing there, neither the collars, nor the ornaments for the breast, nor the bracelets, nor the petticoats ornamented with brass beads. She said, “Come out; the things are no longer here.” All went out. Utombinde, the princess, said, “What can we do?” One of the girls said, “Let us petition. The things have been taken away by the Isikqukqumadevu.” Another said, “You, Isikqukqumadevu, give me my things, that I may depart. I have been brought into this trouble by Untombinde, the king’s child, who said, ‘Men bathe in the great pool: our first fathers bathed there.’ Is it I who bring down upon you the Intontela?” The Isikqukqumadevu gave her the petticoat. Another girl began, and besought the Isikqukqumadevu: she said, “You, Isikqukqumadevu, just give me my things, that I may depart. I have been brought into this trouble by Untombinde, the king’s child; she said, ‘At the great pool men bathe: our first fathers used to bathe there.’ Is it I who have brought down upon you Intontela?” The whole marriage company began until every one of them had done the same. There remained Untombinde, the king’s child, only brought into this trouble by Utombinde, the king’s child; she said, ‘At the great pool men bathe: our first fathers used to bathe there.’ Is it I who have brought down upon you Intontela?”

The marriage party said, “Beseech Usikqukqumadevu, Utombinde.” She refused, and said, “I will never beseech the Isikqukqumadevu, I being the king’s child.” The Isikqukqumadevu seized her, and put her into the pool.

The other girls cried, and cried, and then went home. When they arrived, they said, Untombinde has been taken away by the Isikqukqumadevu.” Her father said, “A long time ago I told Untombinde so; I refused her, saying, ‘To the Llulange, nothing goes to that place and returns again: it goes there for ever.’ Behold, she goes there for ever.”

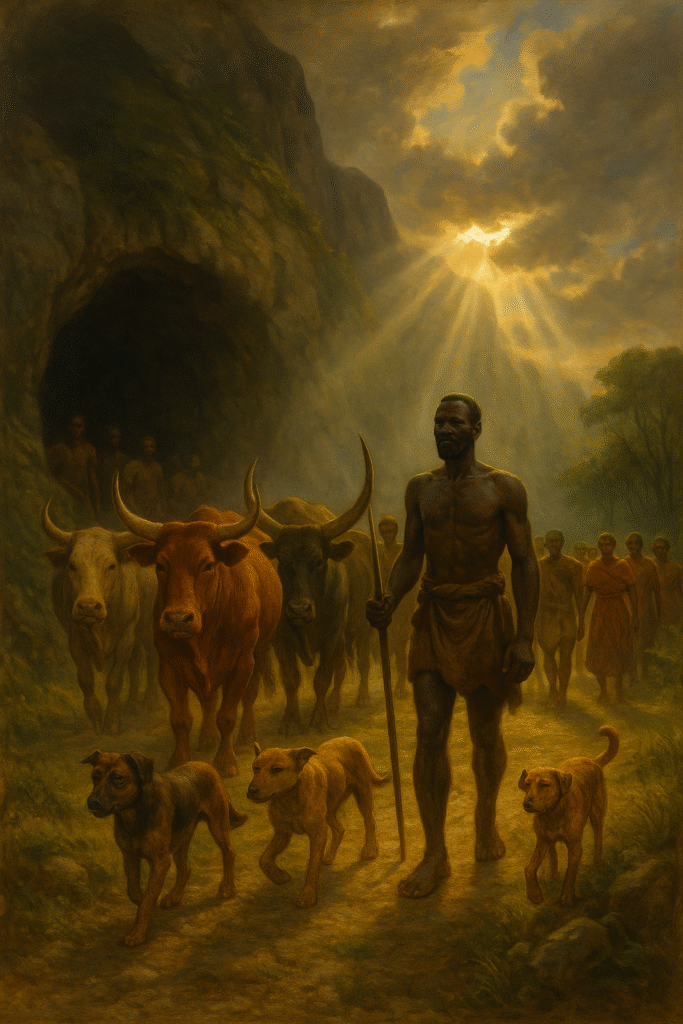

The king mustered the troops of young men, and said, “Go and fetch the Isikqukqumadevu, which has killed Untombinde.” The troops came to the river, and fell in with it, it having already come out of the water, and being now on the bank. It was as big as a mountain. It came and swallowed all that army; and then it went to the very village of the king; it came, and swallowed up all men and dogs; it swallowed them up, the whole country, together with the cattle. It swallowed up two children in that country; they were twins, beautiful children, and much beloved.

But the father escaped from that house; and he went, taking two clubs, saying, “It is I who will kill the Isikqukqumadevu.” And he took his large spear and went on his way. He met with some buffalo, and said “Whither has Isikqukqumadevu gone? She has gone away with my children.”The Buffalo said, “You are seeking Unomabunge, O-gaul’-iminga. Forward! Forward! Mametu!” He then met with some leopards, and said, I am looking for Isikqukqumadevu, who has gone for Unomabunge, O-gaul’-iminga, O-nsiba-zimak-qembe. Forward! Forward! Mametu!” Then he met with an elephant, and said, “I inquire for Isikqukqumadevu, who has gone away with my children. It said, “You mean Unomabunge, O-gaul’-iminga, O-nsiba-bunge herself: the men found her crouched down, being as big as a mountain. And he said, “I am seeking Isikqukqumadevu, who is taking away my children.” And he said, “You are seeking Unomabunge; you are seeking O-gual’iminga, O-nsiba-zimakqembe. Forward! Forward! Mametu!” Then the man came and stabbed the lump; and so the Isikqukqumadevu died.

And then there came out of her cattle, and dogs, and a man, and all the men; and then Untombinde herself came out. And when she had come out, she returned to her father, Usikulumi, the son of Uthlokothloko. When she arrived, she was taken by Unthlatu, the son of Usibilingwana, to be his wife.

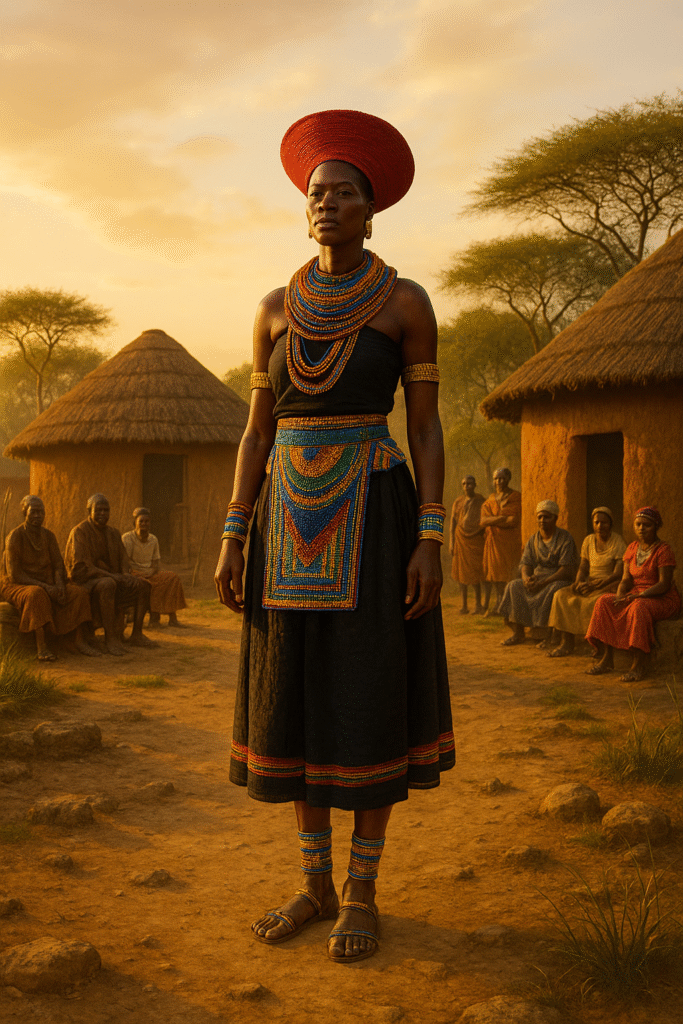

Untombinde went to take her stand in her bridegroom’s kraal. On her arrival she stood at the upper part of the kraal. They asked, “When have you come to marry?” She said, “Unthlatu.” They said, “Where is he!” She said, “I heard said that King Usibilingwana has begotten a king.” They said, “Not so: he is not here. But he did beget a son; but when he was a boy he was lost.” The mother wept, saying, “What did the damsel hear reported? I gave birth to one child; he was lost: there was no other!” The girl remained. The father, the king, said, “Why has she remained?” The people said, “Let her depart.” The king again said, “Let her stay, since there are sons of mine here; she shall become their wife.” The people said, “Let her stay with the mother.” The mother refused, saying, “Let her have a house built for her.” Untombinde therefore had a house built.

It came to pass that, when the house was built, the mother put in it sour milk, and meat, and beer. The girl said, “Why do you put this here?” She said, “I used to place it even before you came.” The girl was silent, and lay down. And in the night Unthlatu came; he took out from the sour milk, he ate the meat, and drank the beer. He stayed a long time, and then went out.

In the morning Utombinde uncovered the sour milk: she found some had been taken out; she uncovered the meat: she saw that it had been eaten; she uncovered the beer: she found that it had been drunk. She said, “O, Mother placed this food here. It will be said that I have stolen it.” The mother came in; she uncovered the food, and said, “What has eaten it?” She said, “I do not know. I too saw that it had been eaten.” She said, Did you not hear the man?” She said, “No.”

The sun set. They ate those three kinds of food. A wether was slaughtered. There was placed meat; there was placed sour milk; and there was placed beer in the house. It became dark, and Untombinde lay down. Unthlatu came in; he felt the damsel’s face. She awoke. He said, “What are you about to do here?” She said, “I come to be married.” He said, “To whom?” The girl said, “To Unthlatu.” He said, “Where is he?” She replied, “He was lost.” He said, “But since he was thus lost, to whom do you marry?” She said, “To him only.” He said, “Do you know that he will come?” He said, “Since there are the king’s other sons, why do you not marry them, rather than wait for a man that is lost?” Then he said, “Eat, let us eat meat.” The girl said, “I do mot yet eat meat.” Unthlatu said, “Not so. As regards me too, your bridegroom gives my people meat before the time of their eating it, and they eat.” He said, “Drink, there is beer.” She said, “I do not yet drink beer; for I have not yet had the imvuma slaughtered for me.” He said, “Not so. Your bridegroom too gives my people beer before they have had anything killed for them.” In the morning he went away; he speaking continually, the girl not seeing him. During all this time he would not allow the girl to light a fire. He went out. The girl arose, going to feel at the wicker door, saying, “Let me feel, since I closed it, where he went out?” She found that it was still closed with her own closing; and said, “Where did the man go out?”

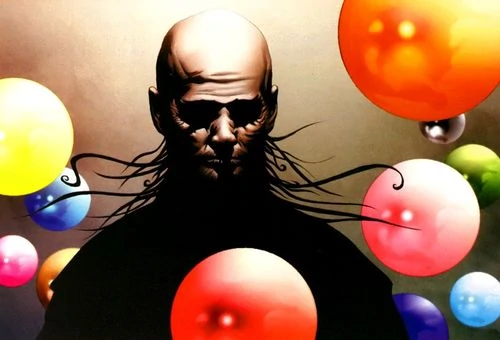

The mother came in the morning, and said, “My friend, with whom were you speaking?” She said, “No; I was speaking with no one.” She said, “Who was eating here of the food?” She said, “I do not know.” They ate that food also. There was brought out food for the third time. They cooked beer and meat, and prepared sour milk. In the evening Unthlatu came, and felt her face, and said, “Awake.” Untombinde awoke. Unthlatu said, “Begin at my foot, and felt me till you come to my head, that you may know what I am like.” The girl felt him; she found that the body was slippery; it would not allow the hands to grasp it. He said, “Do you wish that I should tell you to light the fire?” She said, “Yes.” He said, “Give me some snuff then.” She gave him snuff. He said, “Let me take a pinch from your hand.” He took a pinch, and sniffed it. He spat. The spittle said, “Hail, king! Thou black one! Thou who art as big as the mountains!” He took a pinch; he spat; the spittle said, “Hail, chief! Hail, thou who art as big as the mountains!’ He then said, “Light the fire.” Untombinde lighted it, and saw a shining body. The girl was afraid, and wondered, and said, “I never saw such a body.” He said, “In the morning whom will you say you have seen?” She said, “I shall say that I have seen no one.” He said, “What will you say to that your mother, who gave birth to Unthlatu, because she is troubled at his disappearance? What does your mother say?” She replied, “She weeps, and says, ‘I wonder by whom it has been eaten. Would that I could see the man who eats this food.’ ” He said, “I am going away.” The girl said, “And you, where do you live, since you were lost when a little child?” He said, “I live underground.” She asked, “Why did you go away?” He said, “I went away on account of my brethren: they were saying they would put a clod of earth into my windpipe; for they were jealous, because it was said that I was king. They said, ‘Why should the king be young, while we who are old remain subjects?’

He said to the girl, “Go and call that your mother who is afflicted.” The mother came in with the girl. The mother wept, weeping a little in secret. She said, “What then did I say? I said, ‘It is my child who was lost, who had the smooth body.’ ” He then said, “What will you say to my father?” She said, “I will say, ‘Let the whole country brew beer.’ “

The father said, “What is the beer to do?” The mother said, “I am going to see the people; for I used to be queen. I was deposed because I had no child.” So the beer was brewed; and the people laughed, saying, “She sends for beer. What is she going to do, since she was the rejected one, and was deposed?” The beer was ready; the people came together; the soldiers went into the cattle enclosure; they had shields, and were all there. The father looked on and said, “I shall see presently what the woman is about to do.”

Unthlatu came out. The eyes of the people were dazzled by the brightness of his body. They wondered, and said, “We never saw such a man, whose body does not resemble the body of men.” He sat down. The father wondered. A great festival was kept. Then resounded the shields of Unthlatu, who was as great as all kings. Untombinde was given a leopard’s tail; and the mother the tail of a wild cat; and the festival was kept, Unthlatu being again restored to his position as king. So that is the end of the tale.

[ ZULU ]