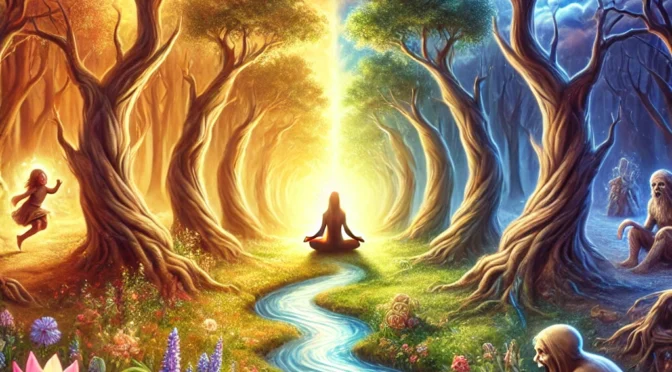

We agree to accept certain data in the physical universe. We agree to form this into certain patterns, and we agree to ignore other data completely. These now, called root assumptions, form the main basis for the apparent permanence and coherence of our physical system.

In your journeys into inner reality, you cannot proceed with these same root assumptions. Reality, per se, changes completely according to the basic root agreements that you accept. One of the root agreements upon which physical reality is based is the assumption that objects have a reality independent of any subjective cause and that these objects, within definite specific limitations, are permanent.

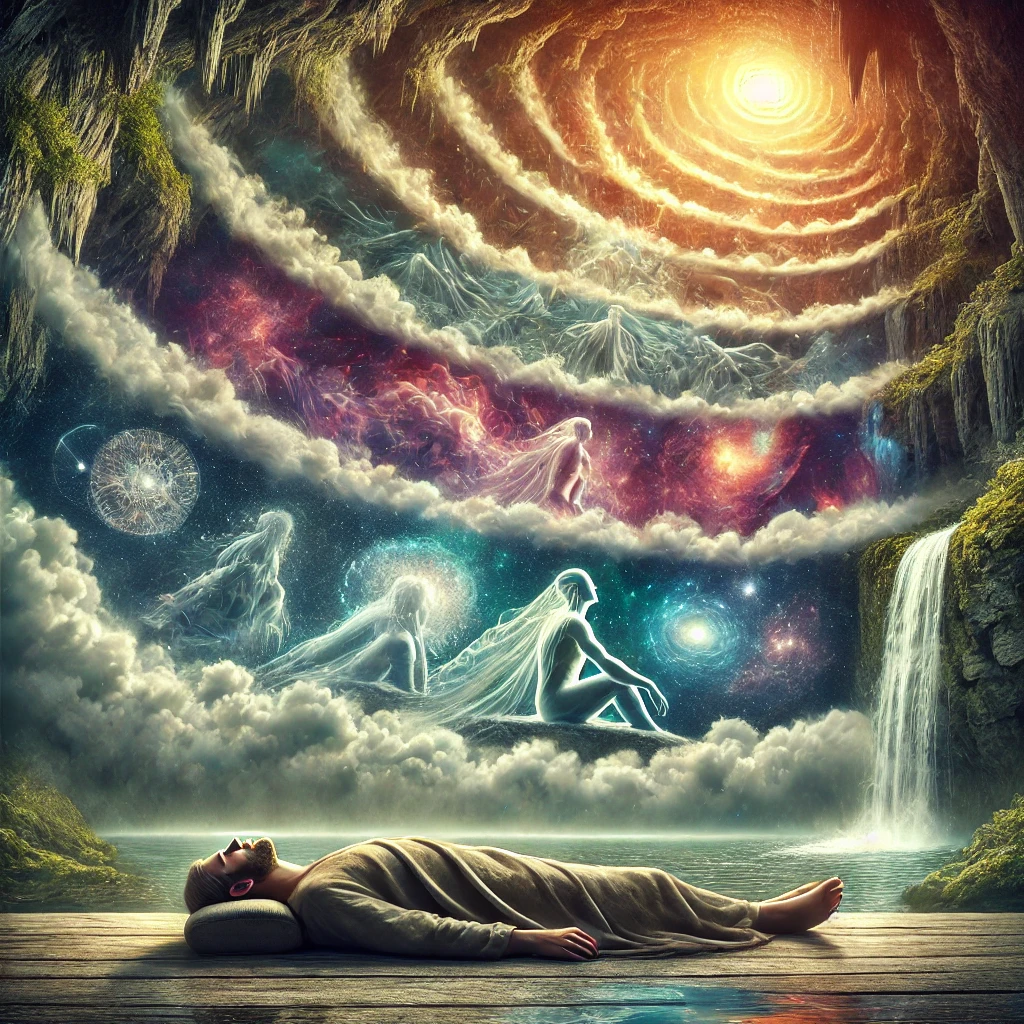

Objects may appear and disappear in these other systems. Using the root assumptions just mentioned as a basis for judging reality, an observer would insist that the objects were not real, for they do not behave as he/she believes objects must. Because dream images may appear and disappear, then, do not take it for granted that they do not really exist.

There is a cohesiveness to the inner universe and to the systems that are not basically physical. But this is based upon an entirely different set of root assumptions and these are the keys that alone will let you manipulate within other systems or understand them. There are several major root assumptions connected here and many minor ones:

- Energy and action are basically the same, although neither must necessarily apply to physical action.

- All objects have their origin basically in mental action. Mental action is directed psychic energy.

- Permanence is not a matter of time. Existence have value in terms of intensities.

- Objects are blocks of energy perceived in a highly specialized manner.

- Stability in time sequence is not a prerequisite requirement for an object, except as a root assumption in the physical universe.

- Space as a barrier does not exist.

- The spacious present is here more available to the senses.

- The only barriers are mental or psychic ones.

Only if these basic root assumptions are taken for granted will your projection experiences make sense to you. Different rules simply apply. Your subjective experience is extremely important here; that is, the vividness of any given experience in terms of intensity will be far more important than anything else.

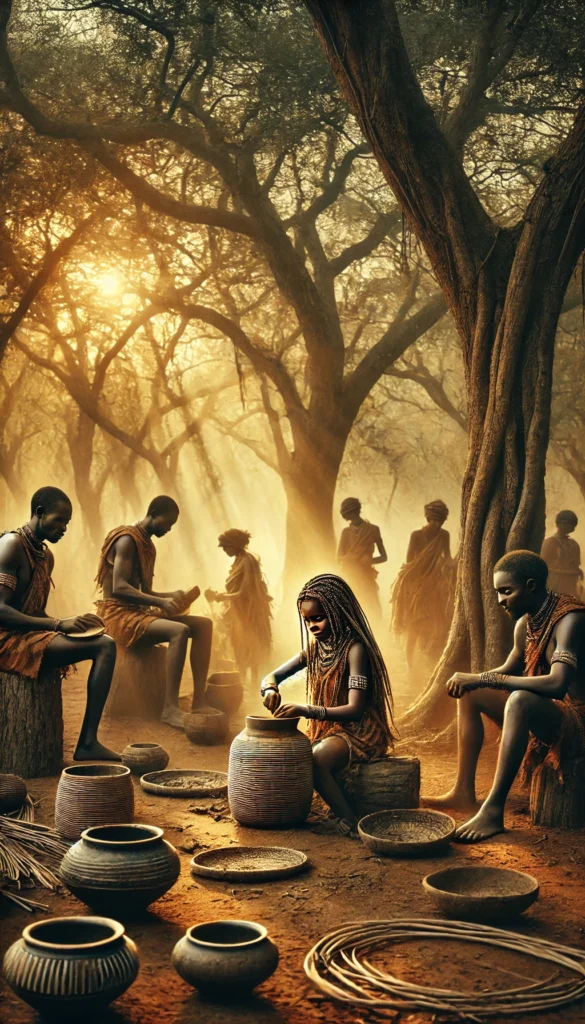

Elements from past, present and future may be indiscriminately available to you. You may be convinced that a given episode is the result of subconscious fabrication, simply because the time sequence is not maintained, and this could be a fine error. In a given dream projection, for example, you may experience an event that is obviously from the physical past, yet within it there may be elements that do not fit. In an old-fashioned room of the 1700’s you may look out and see an automobile pass by. Obviously, you think: distortion. Yet you may be straddling time in such an instance, perceiving, say, the room as it was in the 1700’s and the street as it appears in your present. These elements may appear side by side. The car may suddenly disappear before your eyes, to be replaced by an animal or the whole street may turn into a field.

“This is how dreams work,” you may think. ‘This cannot be a legitimate projection. ‘Yet you may be perceiving the street and the field that existed ‘before’ it, and the image may be transposed one upon the other. If you try to judge such an experience with physical root assumptions, it will be meaningless. As mentioned earlier, you may also perceive a building that will never exist in physical reality. This does not mean that the form is illusion. You are simply in a position where you can pick up and translate the energy pattern before you.

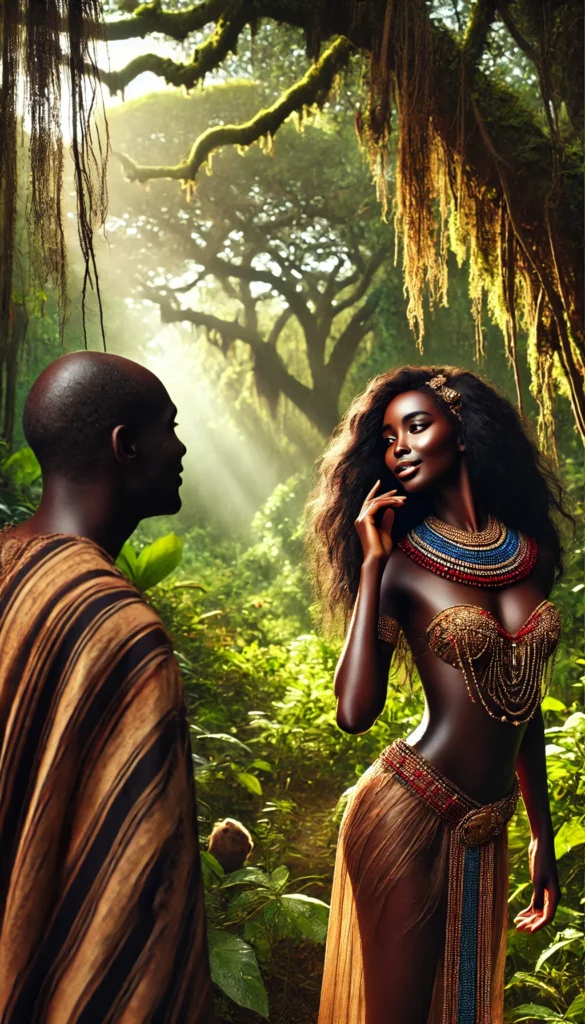

If another individual under the same circumstances comes across the same ‘potential’ object, he/she can also perceive it as you did. He/she may, however, because of his/her own make-up, perceive and translate another portion of allied pattern. He/she may see the form of the man/woman who originated the thought of the building.

To a large extent in the physical system, your habit of perceiving time as a sequence forms the type of experience and also limits it. This habit also unites the experiences, however. The unifying and limiting aspects of consecutive moments are absent in inner reality. Time, in other words, cannot be counted upon to unify action. The unifying elements will be those of your own understanding and abilities. You are not forced to perceive action as a series of moments within inner really, therefore.

Episodes will be related to each other by different methods that will be intuitional, highly selective and psychological. You will find your way through complicated mazes of reality according to your own intuitional nature. You will find what you expect to find. You will seek out what you want from the available data.

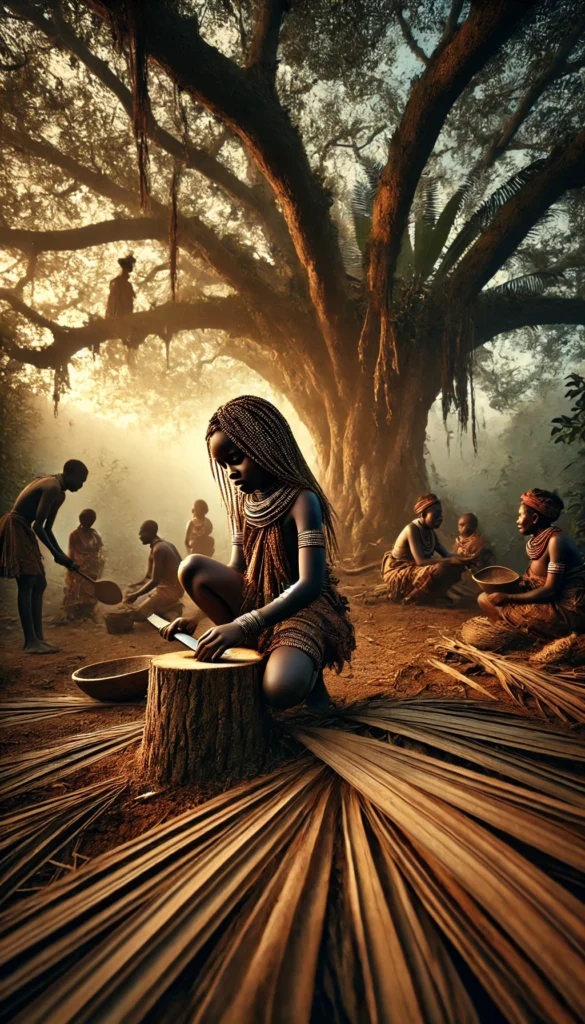

In physical experience, you are dealing with an environment with which you are familiar. You have completely forgotten the chaos and unpredictable nature it presented before learning processes were channeled into its specific directions. You learned to perceive reality in a highly specified fashion. When you are dealing with inner, or basically non-physical realities, you must learn to become unspecialized and then learn a new set of principles. You will soon learn to trust your perceptions, whether or not the experiences seem to make logical sense.

In a projection, the problems will be of a different sort. The form of a man/woman, for example, may be a thought-form, or a fragment sent quite unconsciously by another individual whom it resembles. It may be another projectionist, like yourself. It may be a potential form like any potential object, a record of a form played over and over again.

It may be another version of yourself. We will discuss ways of distinguishing between these. A man/woman may suddenly appear, and be then replaced by a small girl/boy. This would be a nonsensical development to the logical mind; yet, the girl/boy might be the form of the man’s/woman’s previous or future reincarnated self.

The unity, you see, is different. Basically, perception of the spacious present is naturally available. It is your nervous physical mechanism which acts as a limiting device. By acting in this manner it forces you to focus upon what you can perceive with greater intensity.

Our mental processes are formed and developed as a result of this conditioning. The intuitive portions of the personality are not so formed, and these operate to advantage in any inner exploration.

We are basically capable of seeing any particular location as it existed a thousand years in your past or as it will exist a thousand years in your future. The physical senses serve to blot out more aspects of reality than they allow you to perceive, yet, in many inner explorations you will automatically translate experience into terms that the senses can use. Any such translation is, nevertheless, a second-hand version of the original – an important point to remember.