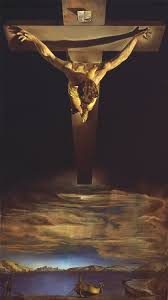

The roman Catholic church gave western civilization its meanings and its precepts.Those meanings and precepts flowed through the entire society, and served as the basis for all of the established modes of knowledge, commerce, medicine, science, and so forth.

The church’s view of reality was the accepted one. I cannot stress too thoroughly the fact that the beliefs of those times structured individual human living, so that the most private events of personal lives were interpreted to mean thus and so, as were of course the events of nations, plants, and animals. The world’s view was a religious one, specified by the church, and its word was truth and fact at the same time.

Illness was suffered, was sent by God to purge the soul, to cleanse the body, to punish the sinner, or simply to teach man and woman his/her place by keeping him or her from the sins of pride. Suffering sent by God was considered a fact of life, then, and a religious truth as well.

Some other civilizations have believed that illness was sent by demons or evil spirits, and that the world was full of good and bad spirits, invisible, intermixed with the elements of nature itself, and that man and woman had to walk a careful line lest he/she upset the more dangerous or mischievous of these entities. In man’s and woman’s history there have been all kinds of incantations, meant to mollify the evil spirits that man believed were real in fact and in religious truth.

It is easy enough to look at those belief structures and shrug our shoulders, wondering at man’s and woman’s distorted views of reality. The entire scientific view of illness, however, is quite as distorted. It is as laboriously conceived and inter-wound with “nonsense.” It is about as factual as the “fact” that God sends illness as punishment, or that illness is the unwanted gift of mischievous demons.

Churchmen and churchwomen of the Middle Ages could draw diagrams of various portions of the human body that were afflicted as the result of indulging in particular sins. Logical minds at one time found those diagrams quite convincing, and patients with certain afflictions in certain areas of the body would confess to having committed the various sins that were involved. The entire structure of beliefs made sense within itself. A man or woman might be born deformed or sickly because of the sins of his or her father.

The scientific framework is basically, now, just as senseless, though within it the facts often seem to prove themselves out, also. There are viruses, for example. Our beliefs become self-evident realities. It would be impossible to discuss human suffering without taking that into consideration. Ideas are transmitted from generation to generation — and those ideas are the carriers of all of our reality, its joys and its agonies. Science, however, is all in all a poor healer. The church’s concept at least gave suffering a kind of dignity: It did come from God — and unwelcome gift, perhaps — but after all it was punishment handed out from a firm father for a child’s own good.

Science disconnected fact from religious truth, of course. In a universe formed by chance, with the survival of the fittest as the main rule of good behavior, illness became a kind of crime against a species itself. It meant we were unfit, and hence brought about all kinds of questions not seriously asked before.

Did those “genetically inferior,” for example, have the right to reproduce? Illness was thought to come like a storm, the result of physical forces against which the individual had little recourse. The “new” Freudian ideas of the unsavory unconscious led further to a new dilemma, for it was then — as it is now — widely believed that as the result of experiences in infancy the subconscious, or unconscious, might very well sabotage the best interests of the conscious personality, and trick it into illness and disaster.

In a way, that concept puts a psychological devil in place of the metaphysical one. If life itself is seen scientifically as having no real meaning, then suffering, of course, must also be seen as meaningless. The individual becomes a victim of chance insofar as his/her birth, the events of his or her life, and his or her death are concerned. Illness becomes his most direct encounter with the seeming meaninglessness of personal existence.

We affect the structure of our body through our thoughts. If we believe in heredity, heredity itself becomes a strong suggestive factor in our life, and can help bring about the precise malady in the body that we believed was there all along, until finally our scientific instruments uncover the “faulty mechanism,” or whatever, and there is the evidence for all to see.

There are obviously some conditions that in our terms are inherited, showing themselves almost instantly after birth, but these are of a very limited number in proportion to those diseases we believe are hereditary — many cancers, heart problems, arthritic or rheumatoid disorders. And in many cases of inherited difficulties, changes could be effected for the better, through the utilization of other mental methods.

There are as many kind of suffering as there are kinds of joy, and there is no one simple answer that can be given. As human creatures we accept the conditions of life. We create from those conditions the experiences of our days. We are born into belief systems as we are born into physical centuries, and part of the entire picture is the freedom of interpreting the experience of life in multitudinous fashions. The meaning, nature, dignity or shame of suffering will be interpreted according to our systems of belief. I hope to give the way a picture of reality that puts suffering in its proper perspective, but it is a most difficult subject to cover because it touches most deeply upon our hopes for oneself and for mankind, and our fears for ourselves and for mankind.

We have taught ourselves to be aware of and to follow only certain portions of our own consciousnesses, so that mentally we consider certain subjects taboo. Thoughts of death and suffering are among those. In a species geared above all to the survival of the fittest, and the competition among species, then any touch of suffering or pain, or thoughts of death, become dishonorable, biologically shameful, cowardly, nearly insane. Life is to be pursued at all costs — not because it is innately meaningful, but because it is the only game going, and it is a game of chance at best. One life is all we have, and that one is everywhere beset by the threat of illness, disaster, and wa — and if we escape such drastic circumstances, then we are still left with a life that is the result of no more than lifeless elements briefly coming into a consciousness and vitality that is bound to end.

In that framework, even the emotions of love and exaltation are seen as no more than the erratic activity of neurons firing, or of chemicals reacting to chemicals. Those beliefs alone bring on suffering. All of science, in our time, has been set up to promote beliefs that run in direct contradiction to the knowledge of man’s and woman’s heart. Science has, we have noted, denied emotional truth. It is not simply that science denies the validity of emotional experience, but that it has believed so firmly that knowledge can only be acquired from the outside, from observing the exterior of nature.

I spoke about the quality of life, and it is true to say that in at least many centuries past, if men and women may have died earlier, they also lived lives of fuller, more satisfying quality — and I do not want to be misinterpreted in the direction.

Now, it is also true that in some of its aspects religion has glorified suffering, elevated it to be one of the prime virtues — and it has degraded it at other times, seeing the ill as possessed by devils, or seeing the insane as less than human. So there are many issues involved.

Science, however, seeing the body as a mechanism, has promoted the idea that consciousness is trapped within a mechanical model, that man’s and woman’s suffering is mechanically caused in that regard: We simple give the machine some better parts and all will be well. Science also operates as magic, of course, so on some occasions the belief in science itself will seemingly work miracles: The new heart will give a man or woman new heart, for example.

Illness is used as a part of man’s and woman’s motivations. What I mean is that there is no human motivation that may not at some time be involved with illness, for often it is a means to a desired end — a method of achieving something a person thinks may not be achieved otherwise.

One man or woman might use it to achieve success. One might use it to achieve failure. a person might use it as a means of showing pride of humility, of looking for attention or escaping it. Illness is often another mode of expression, but nowhere does science mention that illness might have its purpose, or its groups of purposes, and I do not mean that the purposes themselves are necessarily derogatory. Illnesses are often misguided attempts to attain something the person thinks important. Sickness can be a badge of honor or dishonor — but there can be no question when we look at the human picture, that to a certain extent, but an important one, suffering not only has its purposes and uses, but is actively sought for one reason or another.

Most people do not seek out suffering’s extreme experience, but within those extremes there are multitudinous degrees of stimuli that could be considered painful, that are actively sought. Man’s and woman’s involvement in sports is an instant example, of course, where society’s rewards and the promise of spectacular bodily achievement lead athletes into activities that would be considered most painful by the ordinary individual. People climb mountains, willingly undergoing a good bit of suffering in the pursuit of such goals.

Determining not to worry should be the “first commandment.”

I hope I have touched upon a question that’s loaded with ethical and legal dilemmas; many of these have grown out of recent scientific advances in genetics. some moral philosophers, medical geneticists, physicians, lawyers, and religious leaders believe that those who carry genes for serious genetic diseases do not have the right to reproduce. Others of similar background maintain just the opposite — that the right to recreate one’s kind is inalienable. Questions abound involving amniocentesis (examination of the fluid in the womb to detect genetic defects in the fetus); therapeutic abortion; artificial insemination; reproduction by in vitro fertilization; embryo transfer (surrogate motherhood); the responsibilities of the legal, medical and religious communities; whether mentally retarded, genetically defective people should receive life-prolonging medical treatment, and so forth. Years are expected to pass before our legal system alone catches up with the scientific progress in genetics — but ironically, continuing advances in the field are bound to complicate even further the whole series of questions.