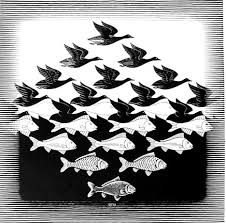

It is not that we overuse the intellect as a culture, but that we rely upon it to the exclusion of all other faculties in our approach to life.

The intellect is brilliant, but on its own, it is indeed in its way isolated both in time and in space in a way that other portions of the personality are not. When it is overly stressed, with all of the usual frameworks or rationales that go along with it, it can indeed become frightened, paranoid, because it cannot really perceive events until they have already occurred. It does not know what will happen tomorrow, and since it is overly stressed, its paranoid tendencies can only fear the worst.

Now those tendencies are not natural to the intellect, but only appear when it is forced to operate in such an isolated fashion — isolated not only in time and space, but psychologically isolated from other portions of the personality that are meant to bring it additional information that it does not possess, and a kind of magical support.

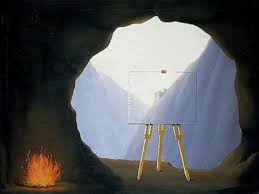

The so-called rational approach to life, as it is practiced, is a highly pessimistic one carrying along with it its own methods and “solutions” to problems, its own means of achieving ends and satisfying desires. Many people are so steeped in that approach to life that they become psychologically blind to any other kind of orientation. Such is obviously not the case for me or I would not be having this discussion, or any other such activity.

The rational approach of course suits certain kinds of people better than others, even while it still carries its disadvantages. We have been living in an industrialized scientific society, so that the benefits and the great disadvantages of the rational approach appear everywhere in the social and political world. Artists of any kind find such an approach the least friendly, for it directly contradicts the vast thrust or man’s and woman’s creativity in several important areas. I, however, have evidence that hardened reality is quite different. In the past I have felt at some disadvantage myself, feeling ,my work to be theoretically fascinating, creatively valid, but not necessarily containing any statement about any kind of “scientifically valid” hardened reality.

I did not think I was dealing with fiction. On the other hand, I was not willing to call is fact, either. I am, in fact, dealing with a larger version of fact from which the world of fact emerges.

There have been numerous fascinating bits of evidence in our own lives, apart from these blog discussions, though certainly to some extent stimulated by the knowledge we gain in the discussions. They remain isolated bits, odds and ends, in which case they begin to present us with a larger factual representation of reality.

All of this material applies to our lives in general and to my physical condition, because we must be clear in our minds as to our own status in that regard, and much of this material will clear the air and dissolve lingering doubts; doubts that cause us to hold on to the rational approach in a misguided effort to maintain what we think of as a balanced viewpoint and open mind. It seems, because of the definitions we have been taught, that there is only one narrow kind of rationality, and that if we forsake the boundary of that narrow definition, then we become irrational, fanatic, mad, or whatever.

The thin, cold “rationality” that is recognized as such is instead a fake veneer covering a far deeper spontaneous rationality, and it is the existence of that magical rationality that provides the basis for the intellect to begin with. The rationality that we accept is then but one small clue as to the spontaneous inner rationality that is a part of each natural person.

For example, in one dream when asleep, when we are seemingly not rational, when our intellect is seemingly not operating, we perceive information about our physical environment. Old neighborhoods, animals and industry in every place. Symbolically we see situations in our own fashion, but know. We still have a love of certain areas. We are in a certain correspondence with it. In a fashion, we keep our eye out for information regarding it.

We are somewhat idealizing the past, present and future, however, so we do not simply get the information “straight on,” but we receive it in such a fashion that it makes its own psychological points also, and is furthermore wound into other action not only within the dream, but in a series of dreams.

Any dream makes it’s point, in fact, whether or not we remembered it. Some people remember because they want to bring into their conscious range instances of their own greater knowing. The portion of us that form the dreams knows. All of this involves a psychological motion of natural, magical import. It shows us that the rules of the rational world are filled with holes. It shows us that the rational world’s views do not represent the bulwarks of safety, but are instead barriers to the full use of the intellect, and of the intuitions.

Free flow of information at other levels.

Now when we understand that intellectually, then the intellect can take it for granted that its own information is not all the information we possess. It can realize that its own knowledge represents the tip of the iceberg. As we apply that realization to our life we begin to realize furthermore that in practical terms we are indeed supported by a greater body of knowledge that we consciously realize, and by the magical, spontaneous fountain of action that forms our existence. The intellect can then realize that it does not have to go it all alone. Everything does not have to be reasoned out, even to be understood.

This information is factual. I am not forced at times into symbolic statements, but when I am I always say so, and even those statements are my best representations of facts too large for our definitions. The intellect, then, can and does form strong paranoid tendencies when it is put in the position of believing that it must solve all personal problems alone — or nearly — and certainly when it is presented with any picture of worldwide predicaments.

The rational approach, built up around this framework, insists that the best way to solve a problem is to concentrate upon it, to project its effects into the future, to ruminate upon its consequences, “to stare at the bare facts head on.”

This brings about an atmosphere in which the problem is compounded. The intellect on its own — so it seems — must deal not only with the problem today, but with its effects in the projected disastrous tomorrows. This well-intentioned concentration, this determination to solve the problem, this rational approach, then causes an even deeper sense of inadequacy. The concentration upon the problem brings about a kind of mechanical repetition, a repeated type of hypnotic focus.

The intellect is a great organizer — along certain lines, now — so if this concentration is continued it begins to organize its perceptions and experience along the same lines. It is a kind of misguided attempt to find order by finding data that agree with itself. It collects evidence, then, to prove its point, because the rational mind, as we understand it, must have an acceptable reason for everything.

In the meantime, of course, quite valid rockbed evidence that does not fit into the picture gradually becomes discarded, ignored, thrown away. It is there but it is not used. It disappears as evidence, becomes inactive. That method of problem-solving, need I say, is a poor one, and if anything it causes far more problems than it ever solves.

In terms of a physical condition, some people often thinks that he or she is “faced with the evidence” that his or her condition is not improving, that it is growing worse, that all the evidence says such conditions do deteriorate rather than improve. He or she sometimes thinks he or she is being rational with such thoughts.

What happens, of course, is the process I have just outlined. Other quite real, quite physical evidence — always, now, apparent in his or her body at any given time — is ignored as nonessential, too trivial to bother with, or take seriously, because it does not fit into the so-called rational picture that has been developed.

The process is exactly as given in the paragraph above, so I want that understood. Any improvement, unless stated, is almost overlooked, not considered as much hard evidence, while any difficulties definitely are considered hard evidence because they fit into the overall data-collecting intellect, as stated above. They are significant, while the improvements do not seem to be nearly as much so.

When we are corresponding with the environment, we change our focus point. We change what we consider significant. This blog brings us to the beginning of a discussion of the magical approach to life, to the solving of problems. I hope to stress what to do, rather than what not to do, although at times I must make the distinction clear.

If you understand this blog thoroughly, and if you have the intent to really change your orientation, then the atmosphere will automatically be created in which desired changes occur.