In all forms of life each individual is born into a world already provided for it, with circumstances favorable to its growth and development; a world in which its own existence rests upon and development; a world in which its own existence rests upon the equally valid existence of all other individuals and species, so that each contributes to nature’s whole.

In that environment there is a cooperative sociability of a biological nature, that is understood by the animals in their way, and taken for granted by the young of our own species. The means are given so that the needs of the individual can be met. The granting of those needs furthers the development of the individual, its species, and by inference all others in the fabric of nature.

Survival , of course, is important, but it is not the prime purpose of a species, in that it is a necessary means by which that species can attain its main goals. Of course [a species] must survive to do so, but it will, however, purposefully avoid survival if the conditions are not practically favorable to maintain the quality of life or existence that it considered basic.

A species that senses a lack of this quality can in one way or another destroy its offspring — not because they could not survive otherwise, but because the quality of that survival would bring about vast suffering, for example, so distorting the nature of life as to almost make a mockery of it. Each species seeks for the development of its abilities and capacities in a framework in which safety is a medium for action. Danger in that context exists under certain conditions clearly known to the animals, clearly defined: The prey of another animal does not fear the “hunter” when the hunter animal is full of belly, nor will the hunter then attack.

There are also emotional interactions among the animals that completely escape us, and biological mechanisms, so that animals felled as natural prey by other animals “understand” their part in nature. They do not anticipate death before it happens, however. The fatal act propels the consciousness out from the flesh, so that in those terms it is merciful.

During their lifetimes animals in their natural state enjoy their vigor and accept their worth. They regulate their own births — and their own deaths. The quality of their lives is such that their abilities are challenged. They enjoy contrasts: that between rest and motion, heat and cold, being in direct contact with natural phenomena that everywhere quickens their experience. They will migrate is necessary to seek conditions more auspicious. They are aware of approaching natural disasters, and when possible will leave such areas. They will protect their own, and according to circumstances and conditions they will tend their own wounded. Even in contests between young and old males for control of a group, under natural conditions the loser is seldom killed. Dangers are pinpointed clearly so that bodily reactions are concise.

The animal knows he has the right to exist, and a place in the fabric of nature. This sense of biological integrity supports him or her.

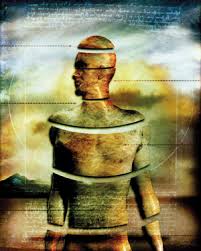

Man and woman, on the other hand , have more to contend with. He or she must deal with beliefs and feelings often so ambiguous that no clear line of action seems possible. The body often does not know how to react. If we believe that the body is sinful, for example, we cannot expect to be happy, and health will most likely elude us, for our dark beliefs will blemish the psychological and biological integrity with which we were born.

The species is in a state of transition, one of many. This one began, generally speaking, when the species tried to step apart from nature in order to develop the unique kind of consciousness that is presently our own. That consciousness is not a finished product, however, but one meant to change, [to] evolve and develop. Certain artificial divisions were made along the way that must now be dispensed with.

We must return, wiser creatures, to the nature that spawned us — not only as loving caretakers but as partners with the other species of the earth. We must discover once again the spirituality of our biological heritage. The majority of accepted beliefs — religious, scientific, and cultural — have tended to stress a sense of powerlessness, impotence, and impending doom — a picture in which man/woman and his/her world is an accidental production with little meaning, isolated yet seemingly ruled by a capricious God. Life is seen as “a valley of tears” — almost as a low-grade infection from which the soul can be cured only by death.

Religious, scientific, medical, and cultural communications stress the existence of danger, minimize the purpose of the species or of any individual member of it, or see mankind/womankind as the one erratic, half-insane member of an otherwise orderly realm of nature. Any or all of the above beliefs are held by various systems of thought. All of these, however, strain the individual’s biological sense of integrity, reinforce ideas of danger, and shrink the area of psychological safety that is necessary to maintain the quality possible in life. The body’s defense systems become confused to varying degrees.

I do not intend to give a treatise upon the biological structures of the body and their inter-workings, but only to add such information in that line that is not currently known, and is otherwise important to the ideas I have in mind. I am far more concerned with more basic issues. The body’s defenses will take care of themselves if they are allowed to, and if the psychological air is cleared of the true “carriers” of disease.